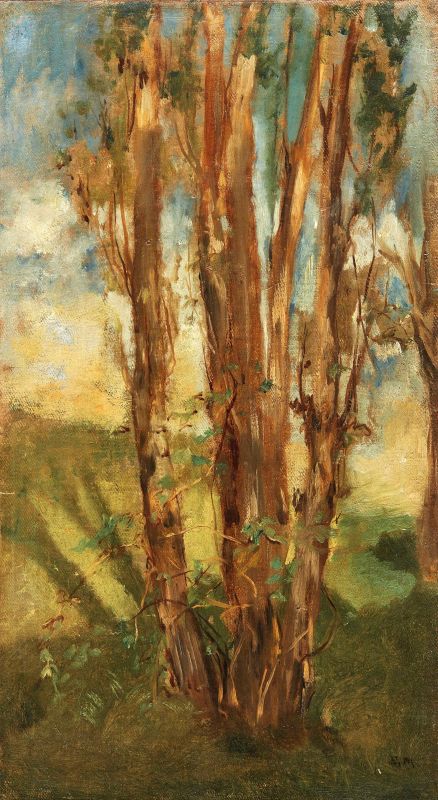

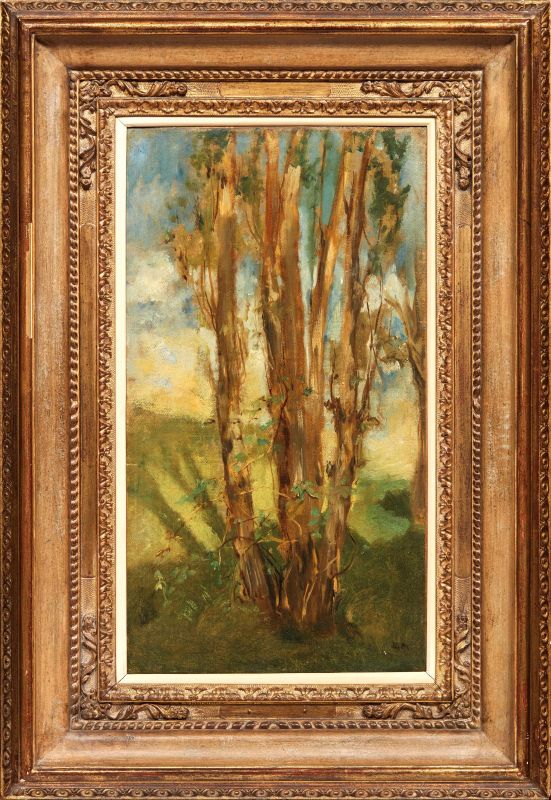

Édouard Manet

(Paris 1832 - 1883)

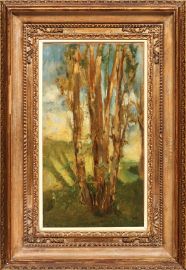

ÉTUDE D’ARBRES

1859 circa

siglato in basso a destra

olio su tela

cm 53,6x 29,8

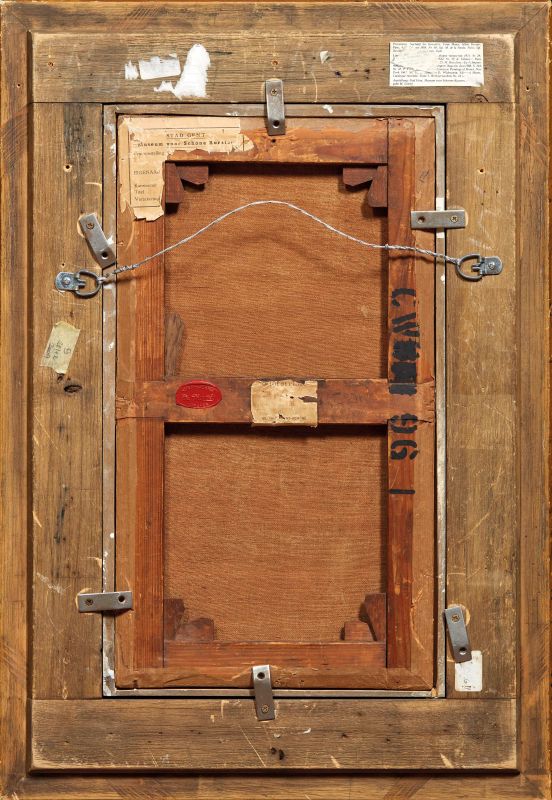

sul retro: sul telaio etichetta del Museum vor Schone Kunsten di Gent, etichetta della Galerie de l’Elysee di Paris e timbro in ceralacca della Kunstgalerij De Vuyst di Lokeren

ÉTUDE D’ARBRES

circa 1859

signed with initials lower right

oil on canvas

21 1/8 by 11 ¾ in

on the reverse: on the stretcher label of the Museum vor Schone Kunsten of Gent, label of the Galerie de l’Elysée in Paris and wax seal of the Kunstgalerij De Vuyst in Lokeren

L’opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Provenienza

Studio dell’artista (inventariato dopo la morte dell’artista)

Hotel Drouot, Paris, Catalogue de tableaux, pastels, etudes, dessins, gravures par Edouard Manet et dépendant de sa succession, 4 – 5 febbraio 1884, lotto 68

Paris, collezione M. de la Narde Bruxelles, collezione A.M. Devillez Gent, collezione M. Leten

Esposizioni

La peinture dans les collections gantoises, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Gent, 28 marzo – 31 maggio 1953.

Bibliografia

E. Moreau-Nelaton, Manet, raconté par luimême, Paris 1926, n. 24.

A. Tabarant, Manet. Histoire catalographique, Paris 1931, p. 48, n. 25.

P. Jamot, G. Wildenstein, Manet, Paris 1932, vol. I, p. 124, n. 76; vol. II, p. 218, fig. 466.

A. Tabarant, Manet et ses oeuvres, Paris 1947, p. 27, n. 25.

S. Orienti, L’opera pittorica di Édouard Manet, Milano 1967, p. 88, n. 18.

M. Bodelsen, Early Impressionist Sales, 1874-1894, in the light of some unpublished ‘procès-verbaux’, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CX, 1968, 783, pp. 330-349: 344, n. 68.

D. Rouart, S. Orienti, Tout l’oeuvre peint d’Édouard Manet, Paris 1970, n. 18.

D. Rouart, D. Wildenstein, Édouard Manet catalogue raisonné. 1. Peintures, Lausanne 1975, pp. 42-43, tav. 24.

Nel 1883, l’anno prima della vendita Manet avvenuta nel febbraio del 1884 all’Hôtel Drouot di Parigi, Léon Koëlla, figlio di Suzanne Leenhoff, la pianista olandese che Édouard Manet aveva sposato vent’anni prima, annotava su una fotografia di questo dipinto custodita negli album Lochard: “Etude pour Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe”. Siamo quindi nella delicata fase in cui, dopo un periodo di apprendimento dalla pittura storica più volte copiata – per esempio Lezione di anatomia di Rembrandt o La Venere di Urbino di Tiziano, entrambi realizzati nel 1856 -, il pittore inizia a dimostrare una certa insofferenza ai precetti scolastici appresi alla scuola d’arte di Thomas Couture. Manet inizia quindi a interessarsi a soggetti attuali come Bevitore di assenzio, opera ispirata ad alcuni versi di Baudelaire nei Fleurs du Mal e rifiutata al Salon del 1859. Anche Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863, Parigi, Musée d’Orsay) nasce dall’istantaneità di un momento colto dall’artista durante una passeggiata. Nei Souvenirs di Antonin Proust, il suo biografo e amico, si legge infatti che, mentre si trovava sulle rive della Senna vicino ad Argenteuil e osservava delle donne intente a bagnarsi, Manet ebbe l’idea di dipingere un nudo ≪dans la transparence de l’atmosphère, avec des personnes comme celles que nous voyons là-bas≫. La sua attenzione per la vegetazione caratterizzata, come nel nostro caso, da alberi che si stagliano in un cielo azzurro e luminoso, non manca nei dipinti compiuti alla fine degli anni Cinquanta, ed è al 1859 che gli studiosi datano anche quest’opera. Diventa quindi difficile sostenere che si tratti di uno studio per l’ambientazione del celebre capolavoro manettiano risalente al 1863. A quell’epoca Léon Koëlla, nato nel gennaio del 1852, era un bambino. Lo troviamo ritratto in La pêche (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) prima ancora che Manet sposasse sua madre Suzanne. Secondo Duret, La pêche risale proprio al 1859 (Histoire d’Edouard Manet et de son oeuvre, 1902, p.100), per cui il nostro studio potrebbe essere riconducibile a questo dipinto oppure a Gli studenti di Salamanca (1860, Hakone, Pola Museum of Art) in cerca di un tesoro nel paesaggio ispirato ai dintorni di Parigi. Diversi schizzi e disegni all’acquerello di alberi presenti in carnet appartenenti al pittore e realizzati dal 1859 in poi dimostrano l’attenzione di Manet per il contesto naturale in cui ambientare le scene all’aria aperta, come Musica alle Tuileries, (Londra, The National Gallery), opera datata 1862. In un noto articolo del 1863, Baudelaire, riferendosi a quest’ultimo quadro, definisce Manet pittore della vita moderna, finalmente libero dalle remore scolastiche e museali. Il poeta più volte lo aveva incitato a scrollarsi di dosso gli schemi legati al passato. Un passato a cui appartiene, almeno in parte, La Nymphe surprise (Buenos Aires, Museo National de Bellas Artes), opera datata 1861 ma cominciata nel 1859 e modificata in corso d’opera. Esiste a riguardo la testimonianza di Antonin Proust (Edouard Manet. Souvenirs, in “La Revue Blanche”, febbraio – marzo 1897, p.168) il quale scrive che nel 1859, prima di lasciare l’atelier di rue Lavoisier, Manet aveva cominciato una grande dipinto, Mosé salvato dalle acque che non aveva completato ed era rimasta solo una figura: la Nymphe surprise. Le fotografie d’epoca mostrano in alto e a destra una figura di satiro, ora non e più visibile. In effetti, la tela è stata mandata a San Pietroburgo nell’autunno del 1861 con il titolo Ninfa e satiro. Anche in questo caso una serie di alberi con fusto liscio e dritto incorniciano il ritratto femminile coprendo con i rami il cielo in parte azzurro.

In 1883, Léon Koëlla, son of Suzanne Leenhoff, the Dutch pianist Édouard Manet had married twenty years earlier, wrote a short note on a photograph of this painting in the Lochard albums: “Etude pour Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe”. It was a year before the February 1884 Manet sale at the Hotel Drouot in Paris and tells us that it was a delicate phase in the artist’s career. After studying and copying old master paintings – such as Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson or the Venus of Urbino by Titian, both done in 1856 - Manet began feeling some intolerance for the rules he had learned in Thomas Couture’s art school. And so, he started to become interested in “current” subjects such as Le Buveur d’absinthe (The Absinthe Drinker) that was inspired by some lines in Charles Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal and was rejected by the 1859 Salon. Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) (1863, Paris, Musée d’Orsay) was also born from the spontaneity of a moment the artist seized during a walk. In Souvenirs, Antonin Proust, his biographer and friend from the days they studied at the Collège Rollin, tells us that one day Manet saw some women bathing in the Seine near Argenteuil, and had the idea of painting a nude «dans la transparence de l’atmosphère, avec des personnes comme celles que nous voyons là-bas». His interest in vegetation and specifically, as in our painting, trees that stand out against a luminous blue sky, also comes through in his works from the late 1850s, and in fact, scholars have dated this piece to 1859. Therefore, it is difficult to maintain the hypothesis that it is a study for the setting of his 1863 masterpiece. Léon Koëlla, born in January 1852 was still a child at the time. We see him portrayed in La peche – (Fishing) (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), before Manet married his mother Suzanne. According to Duret, Manet painted La pêche in 1859 (Histoire d’Edouard Manet et de son oeuvre, 1902, p.100), therefore our study could be connected to that painting or to The Students of Salamanca (1860, Hakone, Pola Museum of Art) hunting for treasure in a landscape inspired by the Paris surroundings. Various sketches and watercolour drawings of trees in the artist’s sketchbooks done after 1859 speak to his interest in natural settings for his outdoor scenes such as Music in the Tuileries Gardens, (London, The National Gallery), which is dated 1862. Referring to the “Music” painting in a famous 1863 article, Baudelaire described Manet as a painter of modern life, finally free of the restraints imposed by schools and museums. On more than one occasion the poet had urged him to shake off the models and moulds linked to the past. That past partially includes La Nymphe surprise – (Nymph Surprised) (Buenos Aires, Museo National de Bellas Artes). Although it is dated 1861, Manet began the painting in 1859 and modified it as he worked. We know this from Antonin Proust (“Edouard Manet. Souvenirs”, in La Revue Blanche, February – March 1897, p.168) who wrote that in 1859, before leaving the atelier on Rue Lavoisier, Manet had begun a large painting, Moses Saved from the Waters, that he never finished and all that remained was a single figure the Nymphe surprise. Period photographs show a satyr at the upper right that is no longer visible. The painting had been sent to Saint Petersburg, with the title Nymph and Satyr in the autumn of 1861. Here too, a group of straight trees with smooth trunks frames the female portrait covering the partially blue sky with branches.