Pablo Picasso © (Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973)

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

(Malaga 1881 - Mougins 1973)

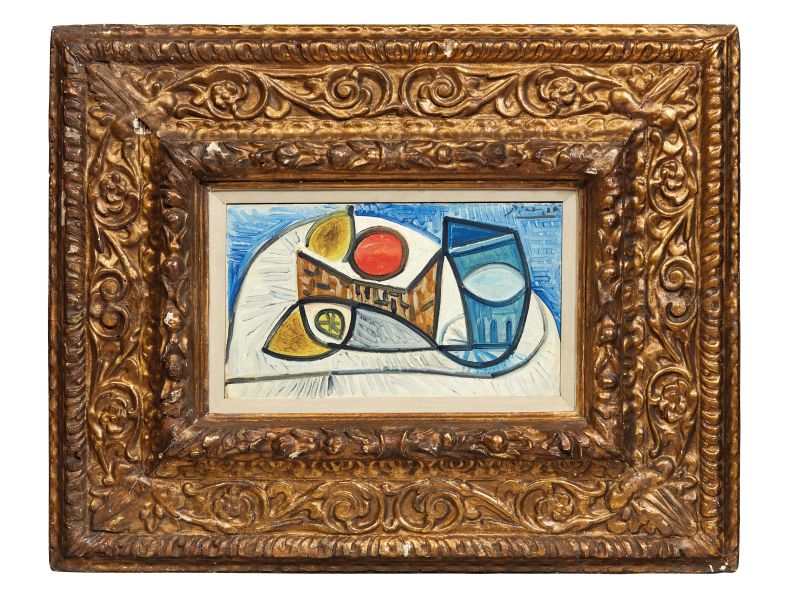

NATURE MORTE AU CITRON, À L’ORANGE ET AU VERRE

1944

firmato in alto a destra

olio su tela

cm 24x40,7

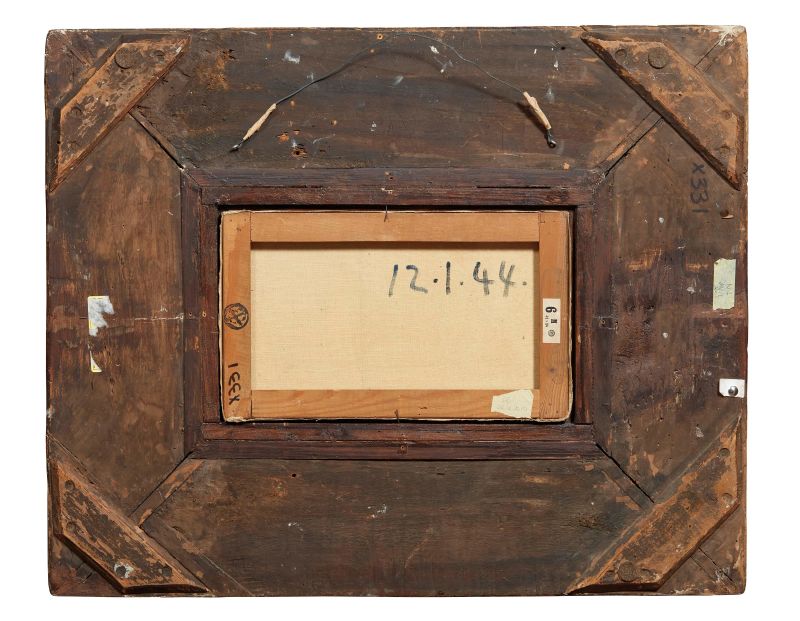

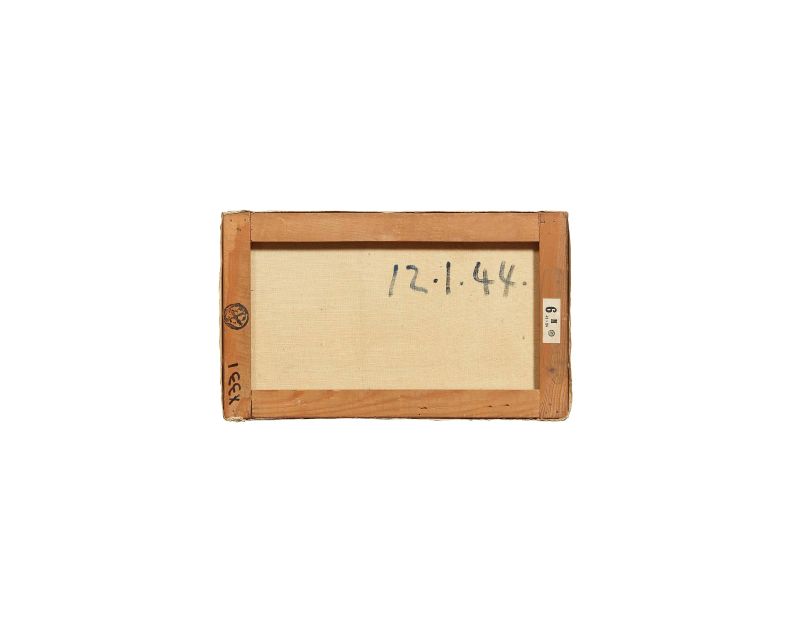

retro: datato “24.1.44”

NATURE MORTE AU CITRON, À L’ORANGE ET AU VERRE

1944

signed upper right

oil on canvas

9 7/16 by 16 1/16 in

on the reverse: dated “24.1.44”

L’opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Provenienza

Sotheby’s, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art, 13 novembre 1996, lotto 331

Bibliografia

C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso, 13. Oeuvres de 1943 et 1944, Paris 1962, p. 112, tav. 228.

Il soggetto della natura morta accompagna l’intero sviluppo espressivo di Picasso lungo tutta la prima metà del Novecento: esso è occasione di sperimentazione costante e banco di prova per le ricerche spaziali e materiche cubiste, dai papiers collés e dagli assemblaggi di materiali di riuso, ai disegni e ai dipinti tra cubismo analitico e sintetico del primo decennio del Novecento, sino alle composizioni degli anni Venti, informate da un rinnovato “neo-classicismo”. La linearità geometrica astraente marca tali esperienze picassiane, ma, come Kandinsky stesso aveva sottolineato ne Lo spirituale nell’arte, a proposito di quelle esperienze cubiste, Picasso dissezionando gli aspetti delle cose non aveva affatto intenzione di allontanarsi dalla loro presenza reale e materiale. Il nostro dipinto reca inscritta sul retro la data della sua esecuzione: 12 gennaio 1944. In piena guerra, in una Parigi ancora occupata dai tedeschi, Picasso lavora nel grande atelier di rue des Grands-Augustins, e vi realizza vedute di Parigi e Nature morte di semplice, ascetica oggettività. Attraverso lo schematismo ideografico, già sperimentato in composizioni “surrealiste” come Pesca notturna ad Antibes del 1939, riduce le forme a puri ideogrammi, imbrigliati da un forte segno di contorno. Quattro anni più tardi dipingerà Cuisine (prima versione: olio su tela, 1948; New York, Museum of Modern Art). Quest’opera di grande rilievo realizzata nel secondo dopoguerra può considerarsi l’apice dello sviluppo evolutivo di una serie di dipinti che mostrano il soggetto della tavola “apparecchiata”, da oggetti e presenze realistico/decorative, evocate nell’ambiente della cucina o della sala da pranzo: metafora dello studio e dello stesso operare dell’artista, nel suo rapporto vitale e passionale con la realtà. Ma se in Cuisine lo schema di un tracciato lineare ha sostituito integralmente la dimensione oggettuale, e la “figura” che percorre l’intera tela è un elastico labirinto di linee-forza, nel nostro quadro gli oggetti campeggiano sul piano rotondo del tavolo, in una sequenza di elementi rilegati da un segno di contorno simile al piombo delle vetrate. Tale ricerca assimila il quadro alla composizione Natura morta con melone, tempera e olio su compensato del 1948 (Torino, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea), che della presente Natura morta può considerarsi prova pittorica più prossima. Un vibrante fondo azzurro, reso con fitto tratteggio, colma ogni spazio vuoto intorno al fulcro della composizione, facendo risaltare il candido piano di posa del tavolo su cui sono deposti alcuni frutti e pochi oggetti. La pennellata è ben visibile, materica e regolare, come se con un’energia costante e misurata il pittore avesse disposto il tracciato elementare, ma vivido, di piccoli ripetuti segni di gessetto per riempire di sostanza cromatica e luminosa il quadro. L’artista pare recuperare la linea arabescata di Matisse, fondendola al rigore astratto-geometrico dei tagli piani e delle sezioni bidimensionali. Il profilo delle cose risalta evidente, accordando la sequenza degli elementi al formato stretto e allungato della tela. Domina una fissa schematicità e, anche, la sottrazione di dettagli mimetici: il tavolo ricoperto di una tovaglia bianca, una arancia, una pera, un bicchiere o anche una brocca con dell’acqua, forse un cestino. Le presenze sono materializzate da “segni” di una povertà esornativa disarmante, tracciati ribaltando sul piano la profondità prospettica, fondendo in linee geometriche l’incastro o la sovrapposizione dei volumi, tanto da esibire una intenzionale ricerca di astrazione. Il ricorso ai colori primari, il giallo, il rosso, il blu, a volte sporcati nella loro purezza o in rapporto sonoro con il bianco, manifesta l’esigenza di ridurre la notazione a pochi, marcati, fondamentali accordi.

The still life as a genre accompanied Picasso’s expressive development through the entire first half of the 20th century: it provided constant occasions for experimentation and a test bench for the artist’s spatial and materic Cubist research, from the papiers collés and the assemblages of recovered materials to the analytical and synthetic Cubist drawings and paintings of the first decade of the 1900s and to the compositions of the 1920s informed by a renewed “neoclassicism”. An “abstracting” geometric linearity marks these of Picasso’s works but, as Wassily Kandinsky had remarked in his Concerning the Spiritual in Art a propos of those Cubist experiences, Picasso, although dissecting the exterior aspects of things, had no intention of divorcing himself from their real and material presence. Our painting is dated on the back: 12 January 1944. With WWII still in full swing, in a Paris still occupied by the Germans, Picasso worked at the huge atelier in Rue des Grands-Augustins, where he painted views of the city and still lifes of simple, ascetic objectivity. Through ideographic schematization, with which he had already experimented in such “surrealist” compositions as Night Fishing at Antibes (1939), he reduced his forms to pure ideograms, bridled by a strong outline sign. Four years after painting our still life, he painted Cuisine (The Kitchen) (first version: oil on canvas, 1948; New York, Museum of Modern Art). This important post-war work may well be considered the apex of the evolutionary development of a series of paintings on the subject of the table “set” with objects and realistic/decorative presences evoked in the setting of the kitchen or the dining room: metaphors for the painter’s studio and his work as part of his vital and impassioned relationship with reality. But while, in Cuisine, the schematic made of linear signs has fully replaced the “object” dimension, and the “figure” that runs through the entire canvas is an elastic labyrinth of force lines, in our painting the objects stand on the round plane of the table as a sequence of elements bound by an outline sign similar to the lead of stained-glass windows. And this research likens the painting to the 1948 Still Life with Melon, in tempera and oils on plywood (Turin, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea), to which our Still Life may be considered very close, pictorially speaking. A vibrant blue background, rendered with a closely-packed parallel brushstrokes and cross-hatching, fills every empty space around the fulcrum of the composition, highlighting the white plane of the table surface on which several pieces of fruit and a few other objects are set. The brushstroke is clearly visible, materic and regular, as though the painter had poured a constant, measured flow of energy into laying down repeats of elementary but vivid, tiny “chalk” marks to fill the space of the canvas with luminous chromatic “substance”. The artists seems to recover Henri Matisse’s arabesque line and to tangle it with the abstract-geometric rigour of the flat planes and two-dimensional sections. The profiles of the objects stand out clearly and adapt the sequence of elements to the rather narrow but elongated format of the canvas. What dominates here is a fixed schematism in a canvas from which mimetic details are subtracted: the table covered with a white cloth, an orange, a pear, a glass and/or a pitcher of water, perhaps a basket. The presences are materialised as “signs” of a disarming decorative poverty, drawn by overturning the perspective depth on the plane, uniting the abutting or superimposed volumes in geometric lines, making it clear that the search for abstraction is intentional. Picasso’s use of primary colours, yellow, red, blue, their purity on occasion muddied or resonating with the white, manifests the painter’s need to reduce the notation to a few, accented, fundamental chords.