Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio Calabria 1882 - Verona 1916)

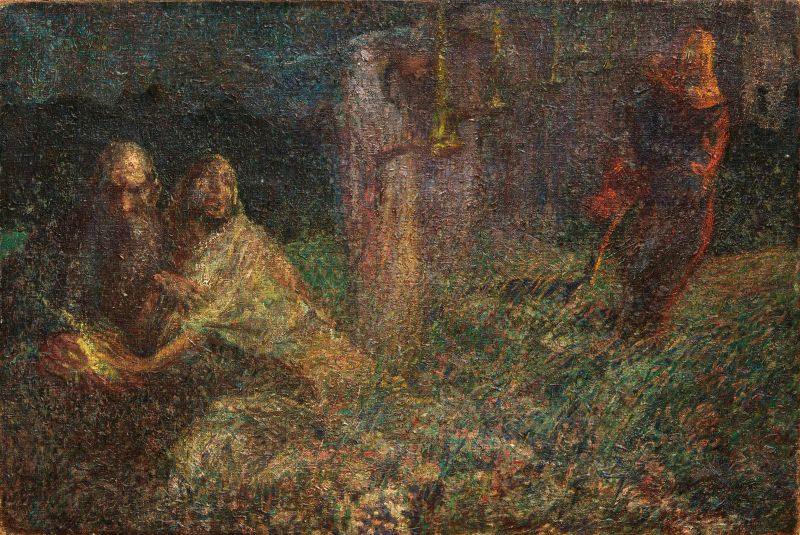

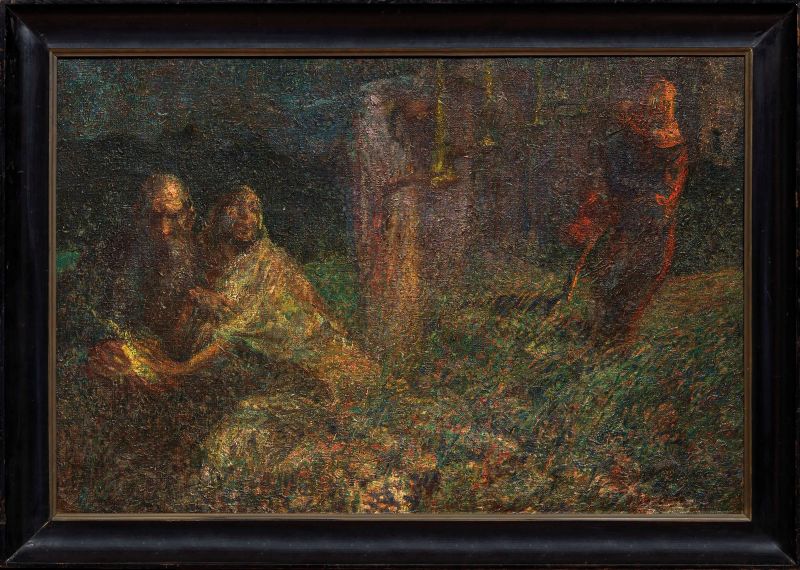

IL FALCIATORE

oppure

ALLEGORIA DELLA VITA

1909

firmato, datato “1909” in basso a destra e dedicato

“A Federico So...”

olio su tela

cm 61,5x91

sul retro: etichetta della Galleria Annunciata di Milano

THE REAPER

or

ALLEGORY OF LIFE

1909

signed and dated “1909” lower right, inscribed “A Federico

So...”

oil on canvas

24 ¼ by 35 9/16 in

on the reverse: label of the Galleria Annunciata in Milan

Provenienza

Milano, collezione Sommaruga

Monza, collezione privata

Milano, collezione privata

Milano, Galleria Annunciata

Esposizioni

Omaggio a Umberto Boccioni, Galleria d’Arte Moderna Falsetti, Cortina d’Ampezzo, 25 dicembre 1971 – 10 gennaio 1972.

Boccioni prefuturista, Museo Nazionale, Reggio Calabria, 5 luglio – 30 settembre 1983.

Umberto Boccioni, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 15 settembre 1988 - 8 gennaio 1989.

Bibliografia

Omaggio a Umberto Boccioni, catalogo della mostra (Galleria d’Arte Moderna Falsetti, Cortina d’Ampezzo, 25 dicembre 1971 – 10 gennaio 1972), Firenze 1971, tav. 5.

M. Calvesi, E. Coen, Boccioni, Milano 1983, p. 302, n. 454.

Boccioni prefuturista, catalogo della mostra (Museo Nazionale, Reggio Calabria, 5 luglio – 30 settembre 1983; Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, Roma, 18 ottobre – 27 novembre 1983) a cura di M. Calvesi, E. Coen e A. Greco, Milano 1983, p. 144, n. 181.

E. Coen, Umberto Boccioni, catalogo della mostra (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 15 settembre 1988 – 8 gennaio 1989), New York 1988, p. 77, tav. 40.

M. Calvesi, Ester l’expert. Leggerezze su Boccioni, in “Storia dell’arte”, CXIX, 2008, pp.131-170: n. 131-132.

Nel 1909, anno della pubblicazione su “Le Figaro” del manifesto del futurismo, Boccioni vive un sincero trasporto per la pittura di Previati cominciato nel 1907 quando, durante un breve soggiorno a Parigi, visita l’esposizione dei Divisionisti. La concezione idealista presente nelle “meravigliose” tele di Segantini e in quelle “arditissime” di Previati, come egli stesso le definisce nel suo diario il 17 ottobre 1907, costituisce ai suoi occhi un’alternativa al verismo fotografico e divisionista di Balla da cui si allontana appuntando lapidario in quelle stesse pagine “Balla e morto”. Nel marzo del 1908 ha un incontro emozionante con Previati, artista particolarmente dedito a soggetti religiosi e allegorici, l’estate prima riceve in regalo una “magnifica” bibbia, da tempo desiderata. In questo contesto nasce Il falciatore, conosciuto anche con il titolo Il cammino della vita, dipinto di tematica simbolista - decadente che ha sollevato, tra gli anni Ottanta e i primi anni Duemila, una serie di contrasti tra gli studiosi di riferimento del pittore. Pubblicata nel catalogo generale di Boccioni edito nel 1983 a firma di Maurizio Calvesi e di Ester Coen, esposta alla fine del 1983 a Reggio Calabria in una mostra a cura degli stessi Calvesi e Coen e di Antonella Greco, poi dalla Coen alla mostra dedicata all’artista presso il Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York nel 1988, l’opera appare, vent’anni dopo, in un articolo scritto da Calvesi tra i lavori erroneamente attribuiti a Boccioni dalla collega (M. Calvesi, Ester l’expert. Leggerezze su Boccioni, in “Storia dell’arte”, n. 119, Roma CAM 2008). Lo studioso sostiene, disconoscendo il proprio parere espresso precedentemente, di trovarsi di fronte alla copia del quadro Parabola delle Vergini sagge e delle Vergini stolte, realizzato da mano anonima nei primi anni del Novecento di cui pubblica la riproduzione, che mostra, per altro, delle similitudini con la pittura boccioniana illustrando in modo piu leggibile del nostro, particolarmente scuro, il soggetto tratto, appunto, dalla parabola del vangelo di Matteo. Eccone la trascrizione: ≪ Il regno dei cieli è simile a dieci vergini che, prese le loro lampade, uscirono incontro allo sposo. Cinque di esse erano stolte e cinque sagge; le stolte presero le lampade, ma non presero con se olio; le sagge invece, insieme alle lampade, presero anche dell’olio in piccoli vasi. Poiché lo sposo tardava, si assopirono tutte e dormirono. A mezzanotte si levò un grido: Ecco lo sposo, andategli incontro! Allora tutte quelle vergini si destarono e prepararono le loro lampade. E le stolte dissero alle sagge: Dateci del vostro olio, perché le nostre lampade si spengono. Ma le sagge risposero: No, che non abbia a mancare per noi e per voi; andate piuttosto dai venditori e compratevene. Ora, mentre quelle andavano per comprare l’olio, arrivò lo sposo e le vergini che erano pronte entrarono con lui alle nozze, e la porta fu chiusa. Più tardi arrivarono anche le altre vergini e incominciarono a dire: Signore, signore, aprici! Ma egli rispose: In verità vi dico: non vi conosco. Vegliate dunque, perché non sapete nè il giorno nè l’ora≫. In entrambi i quadri si notano, a sinistra, le cinque vergini con le lampade accese raffigurate in fila prospettica e sulla destra il falciatore, iconografia della morte. Sullo sfondo si intravvedono delle luci che stanno per spegnersi, mentre in primo piano c’è lo sposo (il Padre Eterno) seduto a terra con una delle giovani. Nella nostra versione è chiaramente visibile il fuoco acceso, simbolo della vita eterna, protetto dalle mani dell’uomo con i capelli grigi e la folta barba. Se è vero che questo soggetto ≪ di derivazione previatesca per la tavolozza e per la maniera divisionista≫ (Calvesi, Coen 1983) mostra un'acromia particolarmente scura per la tecnica utilizzata, circoscritta in prevalenza a toni verdi e viola, che, in verità, già troviamo nelle due tavolette di paesaggio provenienti dalla collezione Ingrao di reminiscenza pellizziana, è anche vero che il nostro quadro è la versione ritenuta finora anonima mostrano dei dettagli simili a quelli di altri dipinti boccioniani, in particolare del Sogno – Paolo e Francesca (1908-09). Non si dimentichi inoltre l’interesse dell’artista per i soggetti allegorici, testimoniato anche di recente nel catalogo generale firmato da Calvesi e Dambruoso (Allemandi, 2016) dove è presente un’intera sezione intitolata Riferimenti letterari e allegorici nell’opera di Boccioni che conta un’ottantina di opere realizzate tra il 1904 e il 1911. Un quadro, quindi, che meriterebbe degli approfondimenti, anche riguardo le indicazioni riportate nel catalogo della mostra di New York sulla provenienza Sommaruga e sulla presenza della firma, accompagnata da un inizio di dedica “A Federico So…”, e della data.

In 1909, the year the Futurist Manifesto was published in Le Figaro, Boccioni was enraptured of Previati’s paintings. That feeling had begun in 1907 when he saw the Divisionist exhibition during a brief stay in Paris. In his eyes, the idealist conception in Giovanni Segantini’s “marvellous” canvases, and in Gaetano Previati’s “very bold” paintings – as he described them in a diary entry dated 17 October 1907, was an alternative to the photographic and divisionist verism of Giacomo Balla from whom he distanced himself with the brief note “Balla is dead” (Balla e morto) in his diary. In March 1908, he had a moving encounter with Previati, an artist particularly devoted to religious and allegorical subjects, and the previous summer he had received a gift of a “magnificent” Bible he had desired for some time. The Reaper, also known as The Allegory of Life, was created in this context. Between the 1980s and the early years of the current century, its symbolistdecadent theme had given rise to a series of conflicts among the main Boccioni scholars. Published in the 1983 general catalogue of Boccioni’s oeuvre written by Maurizio Calvesi and Ester Coen, shown at the end of 1983 in an exhibition in Reggio Calabria curated by Maurizio Calvesi and Ms. Coen and by Antonella Greco, and then shown in the exhibition “Boccioni: A Retrospective” curated by Ms. Coen (1988, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), the painting appeared twenty years later, in an article by Calvesi speaking of works his colleague had incorrectly attributed to Boccioni (M. Calvesi, “Ester l’expert. Leggerezze su Boccioni”, in Storia dell’arte, n. 119, Roma CAM 2008). Rejecting his own previous opinion, Calvesi maintained that it was a copy of an early twentieth-century painting, Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins by an unknown artist. He published a reproduction of “The Parable” which has similarities with Boccioni’s painting, and shows the subject more clearly than our, particularly dark, painting. The subject is based on the parable in the Gospel According to Saint Matthew (Matt. 25:1-13): «At that time the kingdom of heaven will be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish ones took their lamps but did not take any oil with them. The wise ones, however, took oil in small jars along with their lamps. The bridegroom was a long time in coming, and they all became drowsy and fell asleep. At midnight the cry rang out: Here’s the bridegroom! Come out to meet him! Then all the virgins woke up and trimmed their lamps. The foolish ones said to the wise, Give us some of your oil; our lamps are going out. No, they replied, there may not be enough for both us and you. Instead, go to those who sell oil and buy some for yourselves. But while they were on their way to buy the oil, the bridegroom arrived. The virgins who were ready went in with him to the wedding banquet. And the door was shut. Later the others also came. Lord, Lord, they said, open the door for us! But he replied, Truly I tell you, I don’t know you. Therefore keep watch, because you do not know the day or the hour». In both pictures we see the five virgins with lighted lamps in a perspective row to the left, and to the right the reaper, the symbol of death. In the background are lights that are about to go out, while in the foreground is the bridegroom (the Eternal Father) seated on the ground with one of the girls. In our painting we can clearly see the fire, symbol of eternal life, protected by the man with grey hair and thick beard. If it is true that the subject «based on Previati because of the palette and divisionist style» (Calvesi, Coen 1983) is painted in particularly dark colours because of the technique, and limited to mainly greens and purple – colours that we see in the two small landscapes that recall works by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo in the Ingrao Collection, it is equally true that our painting and the version considered anonymous up to now share details similar to those in other works by Boccioni, in particular The Dream: Paolo and Francesca (1908-09). Nor should we forget the artist’s interest in allegorical subjects as also borne out in the recent general catalogue by Maurizio Calvesi and Alberto Dambruoso (Allemandi, 2016) where there is an entire section, “Riferimenti letterari e allegorici nell’opera di Boccioni” [Literary and Allegorical References in Boccioni’s Oeuvre] with about eighty works produced between 1904 and 1911. This painting, therefore, would deserve further study that should extend to the information contained in the 1988 exhibition catalogue concerning its provenance from the Sommaruga, collection in Milan, as well as the signature with the start of a dedication, “A Federico So…” and the date.