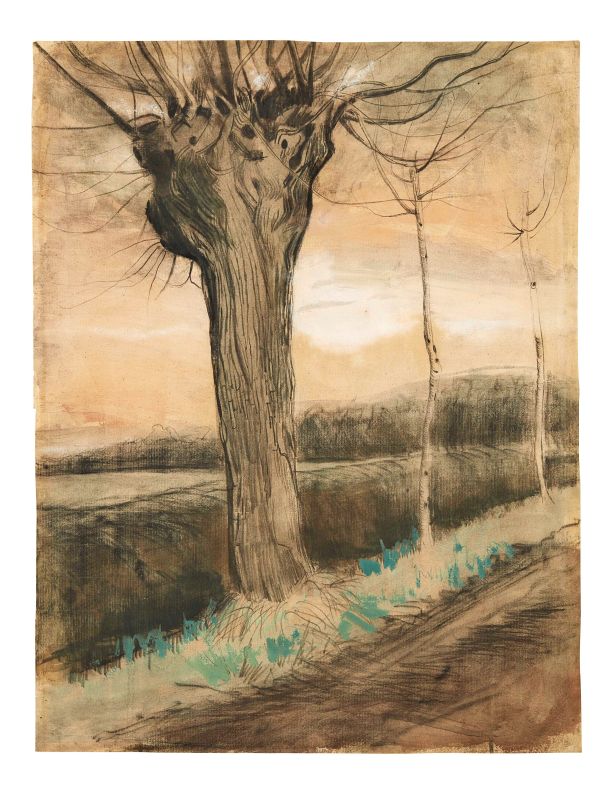

Vincent Van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-oise, 1890)

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

(Zundert 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise 1890)

POLLARD WILLOW

ottobre 1881

gessetto nero, acquerello e biacca su carta

mm 603x465

POLLARD WILLOW

October 1881

black chalk, watercolour on paper heightened with white

23 ¾ by 18 3/8 in

L’opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Provenienza

Noordwijk-a-Zee, collezione M.J.B. Jungmann

Den Haag, collezione M. Gieseler

New York, collezione Julius Joelson

Bibliografia

J.B. de la Faille, L’Oeuvre de Vincent van Gogh. Catalogue raisonné, Paris et Bruxelles 1928, vol. III, p. 40, n. 995; vol. IV, pl. XLI.

J. Hulsker, The new complete Van Gogh. Paintings, drawings, sketches, Amsterdam 1996, p. 24, tav. 56.

Quando realizza quest’opera, van Gogh è all’inizio di una nuova attività: non è più un copiatore ma un libero disegnatore e osservatore della natura. In effetti, prima della visita ad Anton Mauve all’Aja avvenuta nell’estate del 1881, van Gogh si limitava a disegnare quanto già realizzato da altri artisti. Tornato a Etten, doveva vive con i genitori, racconta al fratello Theo: ≪Mauve parve interessarsi soprattutto ai miei disegni. Mi diede molti consigli preziosi e quindi tornerò da lui fra qualche tempo, quando avrò qualcosa di nuovo da sottoporgli≫. Un incontro fondamentale per la sua carriera, che gli suscita forte entusiasmo, tanto che pochi giorni dopo Vincent scrive nuovamente a Theo (n. 150): ≪ho già notizie per te. Devo annunciarti che il mio disegno è cambiato, come tecnica oltre che come risultato. […] Zappatori, seminatori, aratori di entrambi i sessi – ecco ciò che devo disegnare di continuo. Devo osservare e disegnare tutto quello che appartiene alla vita di campagna, come molti altri hanno fatto prima di me e fanno tuttora. Non mi sento più impotente difronte alla natura come un tempo≫. Nella lettera parla anche delle sue sperimentazioni tecniche: ≪Dall’Aia mi sono portato alcuni crayons in legno e li uso molto in questo periodo. Ho anche incominciato a ritoccare il mio lavoro con pennello e sfumino, con un po’ di seppia e inchiostro di China e qua e là con un po’ di colore≫. Tra i vari soggetti disegnati in questo momento nelle sue escursioni in campagna non possono mancare i salici di cui, nella missiva seguente, fa anche uno schizzo. Della serie dedicata al Pollard willow, si ricorda l’acquerello del 1882 (Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) dipinto nei pressi di una stazione ferroviaria, un salice morto sotto il cielo minaccioso e la solitudine di un uomo che cammina lungo la strada avvolto dal cupo paesaggio. Di questo periodo di inizio anni Ottanta è anche il lavoro qui presentato. Nel nostro caso, vediamo l’albero spoglio in primo piano che si staglia contro un cielo nuvoloso dal quale, anche se a fatica, escono i raggi di sole, un segno di speranza e di risurrezione, sottolineato anche dall’erba verde che sta nascendo ai piedi del fusto. Il cerchio della vita continua a girare. E su questo medita van Gogh quando Mauve gli chiede di parlargli non tanto di Jules Dupré, protagonista della scuola di Barbizon, bensì del “ciglio del fosso” o di qualcosa di similare: ≪Non è il linguaggio dei pittori, ma quello della natura che bisogna ascoltare≫ (lettera di luglio 1882).

When he painted this work, van Gogh had just embarked on a new activity: no longer as one who copied, who drew only from the works of other artists – which was the case before his visit to Anton Mauve in The Hague in the summer of 1881 – but as a free draughtsman, an observer and portrayer of nature. Upon his return to Etten, where he lived with his parents, he wrote to his brother Theo: «My own drawings interested Mauve more. He gave me a great many suggestions, which I’m glad of, and I’ve sort of arranged to pay him another visit fairly soon when I have some more studies». That time with Mauve was fundamental for his career. It aroused his enthusiasm, to the point that a bit later he wrote, again to Theo: «…this time I have something more to say to you. Namely that a change has come about in my drawing, both in my manner of doing it and in the result. … Diggers, sowers, ploughers, men and women I must now draw constantly. Examine and draw everything that’s part of a peasant’s life. Just as many others have done and are doing. I’m no longer so powerless in the face of nature as I used to be». In the same letter he also wrote of his technical experiments: «I brought Conté in wood (and pencils as well) from The Hague, and am now working a lot with it. I’m also starting to work with the brush and the stump. With a little sepia or Indian ink, and now and then with a bit of colour». Among the various subjects drawn during this time of excursions into the countryside were the willows, of which he included a sketch in his next letter. Of note in the series devoted the tree is the 1882 watercolour Pollard Willow (Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) painted near a railway station: a dead tree under a menacing sky and a solitary man walking away down the road through the gloomy landscape. The similar work presented here is also from early 1880s; the bare tree in the foreground is outlined against a cloudy sky from which, albeit with difficulty, sunlight breaks out in isolated rays, a sign of hope and resurrection, as is the green grass sprouting at the base of the trunk. The circle of life keeps turning. It was on this thought that van Gogh meditated when he wrote to Theo in 1882 that he better understood Mauve’s request to talk to him not of Jules Dupré, head of the Barbizon school, but instead of the «side of that ditch» or some similar topic, since «It isn’t the language of painters one ought to listen to but the language of nature».