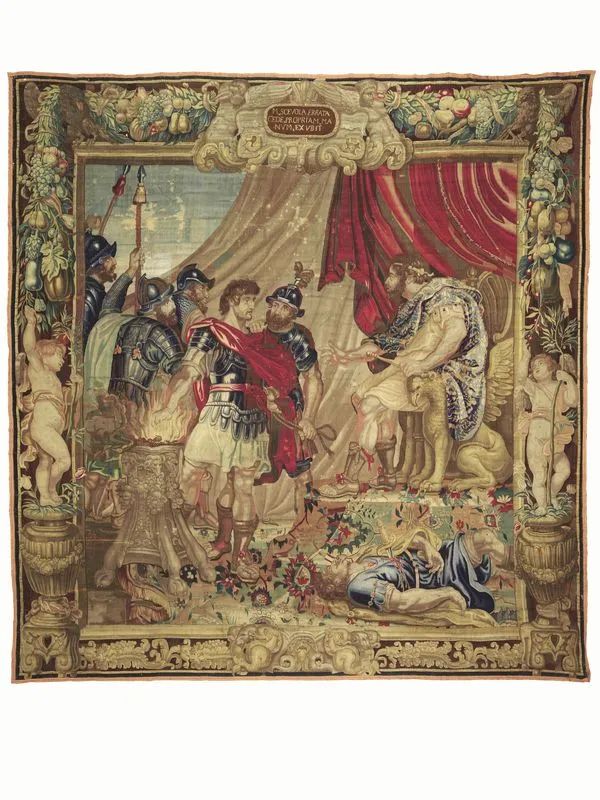

ARAZZO, FIANDRE, METÀ SECOLO XVII

L’eroismo di Muzio Scevola

cm 410x390

TAPESTRY, FLANDERS, MIDDLE OF XVII CENTURY

The heroism of Muzio Scaevola

410x390 cm

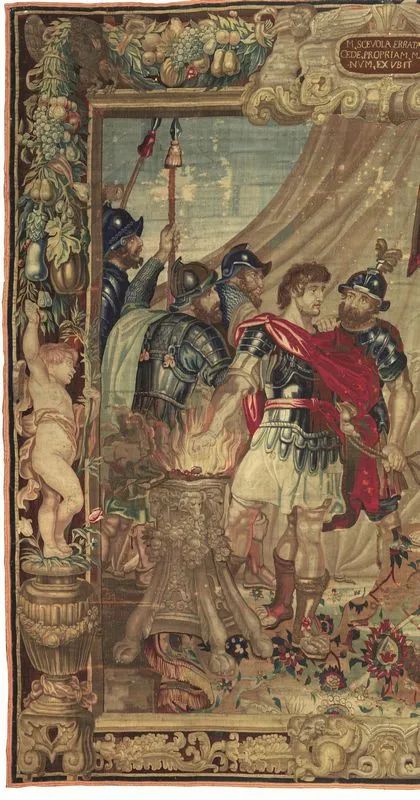

L’arazzo presenta una ricca bordura interamente ricamata con trofei, festoni vegetali e figure: a destra e a sinistra una coppia di putti alati poggianti su basamenti scolpiti a forma di vaso baccellato trattengono nella mano sinistra un alberello, mentre la mano destra è levata verso l'alto, da cui scendono ricchi festoni di fiori e frutta. In alto al centro un ricco cartiglio affiancato da protomi alate, nel cui centro sta l'iscrizione "M.SCEVOLA.ERRATA/CEDE.PROPRIAM. MA/NVM.EXVBIT"; ai margini superiori, tra festoni, sono due aquile. La fascia inferiore infine è decorata con ricchi fregi naturalistici, centrata da un mascherone con figure fantastiche ai lati.

L’episodio storico raffigurato mostra nella parte destra il re etrusco Porsenna seduto in trono e ai suoi piedi il ministro ucciso al suo posto, mentre nella parte sinistra Muzio Scevola, circondato dalle guardie, nell'atto di porre la mano sul fuoco.

Da Tito Livio (Ab urbe condita, libro II, cap. 12) sappiamo che nel 508 a.C., durante l'assedio di Roma da parte degli Etruschi comandati da Porsenna, proprio mentre nella città cominciavano a scarseggiare i viveri, un giovane aristocratico romano, Muzio Cordo, propose al Senato di uccidere il comandante etrusco. Ottenuta l'autorizzazione, si infiltrò nelle linee nemiche, e armato di un pugnale raggiunse l'accampamento di Porsenna, che stava distribuendo la paga ai soldati. Muzio attese che il suo bersaglio rimanesse solo e quindi lo pugnalò: ma sbagliò persona, avendo infatti assassinato lo scriba del re etrusco. Subito venne catturato dalle guardie del comandante, e portato al cospetto di Porsenna, il giovane romano non esitò a dire: «Sono romano e il mio nome è Caio Muzio. Volevo uccidere un nemico da nemico, e morire non mi fa più paura di uccidere… Questo è il valore che da al corpo chi aspira a una grande gloria!” E così dicendo infilò la mano destra in un braciere acceso per un sacrificio e non la tolse fino a che non fu completamente consumata. Da quel giorno il coraggioso nobile romano avrebbe assunto il nome di "Muzio Scevola" (Muzio il mancino). Porsenna rimase tanto impressionato da questo gesto che decise di liberare il giovane. Muzio, allora, sfoggiò la sua astuzia e disse: «Per ringraziarti della tua clemenza, voglio rivelarti che trecento giovani nobili romani hanno solennemente giurato di ucciderti. Il fato ha stabilito che io fossi il primo e ora sono qui davanti a te perché ho fallito. Ma prima o poi qualcuno degli altri duecentonovantanove riuscirà nell'intento». Questa falsa rivelazione spaventò a tal punto il principe e tutta l'aristocrazia etrusca da far loro considerare molto più importante salvaguardare il futuro del re di Chiusi piuttosto che preoccuparsi del destino dei Tarquini. Sempre secondo la leggenda, così Porsenna prese la decisione di intavolare trattative di pace con i Romani, colpito positivamente dal loro valore.

The tapestry has a richly decorated frame border woven with trophies, fruiting garlands and figures: on either side a winged putto is standing on a base in the form of a gadrooned vase and is holding a shrub in his left hand and raising his right hand towards the abundant floral and fruiting swags. At the top, in the centre, there is a cartouche with the inscription "M.SCEVOLA.ERRATA/CEDE.PROPRIAM. MA/NVM.EXVBIT", flanked by two winged figures; two eagles are visible in the top corners, among the garlands. The bottom border is enriched with naturalistic decorations, and a mask flanked by imaginary figures at the centre.

The historical scene to the right represents the Etruscan king Porsena seated on a throne, and at his feet the minister killed in his place, while on the left Mucius Scaevola, surrounded by the guards, is putting his hand into the fire.

We learn from Titus Livius (Ab urbe condita, book II, chapter 12) that in 508 B.C., during the siege of Rome by the Etruscans led by Porsena, and exactly when provisions were starting to run low in the city, a young Roman aristocrat, Mucius Cordus, offered in front of the Senate to kill the Etruscan commander. On obtaining authorization he penetrated the enemy lines, and reached Porsena’s camp armed with a dagger, while the king was giving the soldiers their wages. Mucius waited until his enemy was alone to stab him, but he mistakenly killed the Etruscan king’s scribe instead. He was immediately arrested by the commander’s guards, and once in front of Porsena the young Roman unhesitatingly said: “I’m Roman and my name is Caius Mucius. I wanted to kill an enemy as an enemy, and I’m no less frightened of dying than of killing… this is the value that someone who strives for great glory gives to his own body!” And so speaking he placed his right hand in a brazier which had been lighted for a sacrifice and didn’t remove it until it was totally wasted away. From that day on the brave Roman nobleman would be named “Mucius Scaevola” (Mucius the left-handed). Porsena was so impressed by this gesture that he decided to set the young man free. At that point Mucius displaying his shrewdness said: “To thank you for your mercy, I will reveal to you that three-hundred young Roman noblemen have solemnly sweared to kill you. Destiny decided that I should be the first and I’m in front of you because I have failed. But sooner or later one of the other two hundred and ninety-nine will succeed”. This false revelation frightened the prince and the whole Etruscan aristocracy to such an extent as to decide it was more important to protect the future of the king of Chiusi rather than to worry about the fate of the Tarquins. Again according to legend, Porsena, decided therefore to open peace talks with the Romans, so impressed was he by their valour.