GRANDE VENTAGLIO DECORATO DA DUE ACQUARELLI DI GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 – 1887) E IMPREZIOSITO DA OLTRE 60 IMPORTANTI AUTOGRAFI E DEDICHE, DI CUI 14 AD OPERA DI CELEBRI MAESTRI DI MUSICA, LETTERATI E ATTORI, 1883 – 1993

LARGE FAN DECORATED WITH TWO WATERCOLORS BY GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 - 1887) AND ENHANCED BY OVER 60 IMPORTANT AUTOGRAPHS AND DEDICATIONS, 14 BY FAMOUS MAESTRI, WRITERS AND ACTORS, 1883-1993

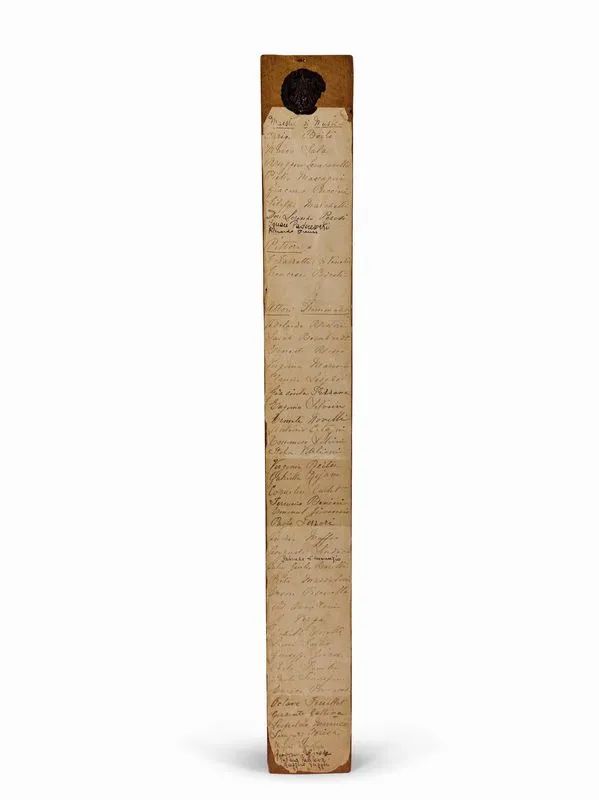

in white paper with top and bottom edges in gold, wooden frame lacquered in red with floral decoration in green and gold on the supporting slats. Width of the open fan: 91 cm. Height: 50 cm. Kept in a specific wooden box with lid (53.2 x 4 x 6.5 cm) with handwritten heading “Gentil Signora Amalia Tibaldi, Verona” and wax seals (one with initials “GV”). The inside of the lid bears a glued white paper strip with a partial list of the names of the authors of dedications and autographs, presumably drawn by the owner of the fan, and complemented by two loose sheets with lists of names stored on the bottom of the box. Light wear.

Over the centuries, the fan has been a typical weapon of feminine seduction. Gestures associated with it even constituted a “language” that allowed to communicate in secret with the male universe. This particular fan, however, perhaps too large to fulfil its traditional task, was used by its owner, Amalia Martinez Tibaldi, as an unusual support for an extraordinary collection of artistic, musical and literary “souvenirs” by great protagonists of Italian culture from 1883 onwards. Thus transformed into a unique and beautiful object, Amalia’s fan bears a more subtle and noble kind of seduction: that of the aesthetic and intellectual pleasure.

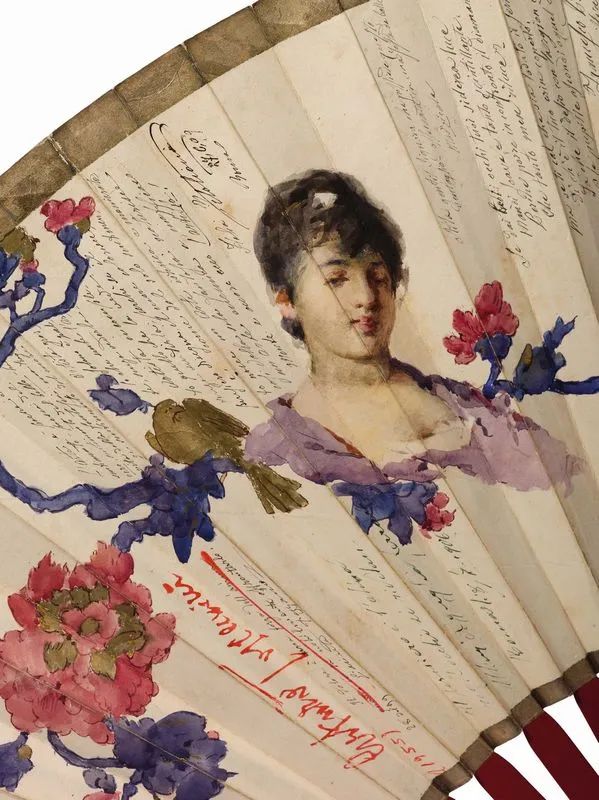

The oldest “souvenirs” date back to 1883. They include two watercolours by Giacomo Favretto, one on each side of the fan, with the portrait of the Japanese lady in kimono bearing the date “1883” under the signature of the artist. The ornamentation of this side of the fan, characterised by flat areas of colour, also includes a floral decoration consisting of branches of flowers and leaves in silver and green, and a small sparrow in flight. On the opposite side, Favretto painted an intense portrait of a lady characterised by muted colours (perhaps Amalia herself?), and purple branches scattered with large flowers and birds in fuchsia and gold. The expression of the woman, who has dark hair and wears a lilac-coloured shawl, is languid, her eyes almost sleepy and her lips slightly parted in a smile.

1883 was also the year of the first of the major autographs of the fan, the one by Giuseppe Giacosa, playwright and librettist, who wrote verses of the comedy The siren, first represented that same year in October. Afterwards, one of our greatest 19th century writers, Giovanni Verga, intervened on Amalia’s fan also quoting one of his plays, the drama In portineria, brought on the Milanese scene in 1885.

The following years, and particularly the last decade of the 19th century, saw the succession of dedications by distinguished maestri, including: Pietro Mascagni in 1892, with musical bars from Cavalleria Rusticana; Giacomo Puccini in 1893, with the famous lines “Manon Lescaut mi chiamo”; Ruggero Leoncavallo in 1896, with the bars of his “ridi pagliaccio”; Arrigo Boito, undated but presumably in the same period, with bars from Il primo Mefistofele; Don Lorenzo Perosi in 1901, with bars from Il Natale del Redentore.

Amalia’s fan is also enriched with many “souvenirs” by theatrical artists, among them Eleonora Duse, who signed it in 1922. Another famous actress, Sarah Bernhardt, in 1899 wrote on it in French “it is women who make men fascinating, full of attentions and good, and your husband is all this”. Name and activity of Amalia’s husband, Eugenio Tibaldi, Lieutenant, can be inferred from other dedications, from which it is also possible to understand that, occasionally, he also asked that the artists contributed to his wife’s fan. A brilliant example is the “souvenir” by the painter Cesare Pascarella, who in 1885 wrote a sonnet in Roman dialect, followed by the phrase (in Italian)[i] “Dear Tibaldi you ask me a sonnet and a donkey for your lady. You’ve read the sonnet ... Here is the donkey ... “And Pascarella added a small self-portrait with monocle and pipe.

The great protagonists of the 20th century who appear on the fan are: Gabriele D'Annunzio, with an autograph dated 1919; Ignacy Jan Paderewski, pianist, composer and Polish politician, with an autograph dated 1932; Richard Strauss, with a signature in green ink, undated; Arturo Toscanini, with a large autograph in red ink, dated 1955; and finally, Luciano Pavarotti, with his typical dedication “per caro ricordo”, dated 1993.

We do not know who continued Amalia Tibaldi’s collection up until recent years (presumably her descendants), neither have we found precise information about this lady and her husband. However, from the dedications one senses much of their lives. Amalia and Eugenio were well integrated into the high society of the time and were passionate about theatre and opera. The fact that Amalia loved to collect dedications on this fan was notorious, as evidenced by the words of journalist Baldassarre Avanzini, who wrote “Either you give me a dedication, or your life! – Amalia demands from behind the slats, in ambush. Here is the dedication! ... No! ... I have not found it ... But my life is here, if you want it.”

Giacinto Gallina, playwright, contributed in a similar way and added a nice quote in French by La Rochefoucauld: “You ask me a thought, my dear Eugene? Here is one by La Rochefoucauld that is also true about friendship: Absence diminishes mediocre passions and increases great ones, as the wind extinguishes candles and fans fires.”

Aware of joining a large group of celebrities, some “souvenirs” playfully underline their own inadequacy. Ferruccio Benini, actor, in May 1900, wrote in a tiny handwriting, not far from the autograph of D’Annunzio, “In this fan there are so many sublime examples of art that I shall put myself here, sheepishly ... so maybe I go unnoticed” Armando Falconi, theatre actor and comedian, in November 1933, snapped in an amusing: “Here I feel like a dog in church!”

Among the other numerous witty dedications, we point out the one by Augusto Sindici, poet, “The woman is born a woman, and into her pupils / The man looks when he is born, and becomes imbecile” and the one by Enrico Panzacchi, poet and critic, “The Heart said to the Brain: / - Why are you up there at the top? - / It was answered - Brother, / To be a lookout, / And to monitor from above / all of the nonsense that you can do”. Finally, we like to quote the beautiful “souvenir” by Renato Fucini, poet and writer, who commented on the fan and on life: “An Archimandrite motto asked the fan: / - Tell me, Fan, what is life? / - And the fan, with much waving: / - It's all wind, wind, wind wind”.