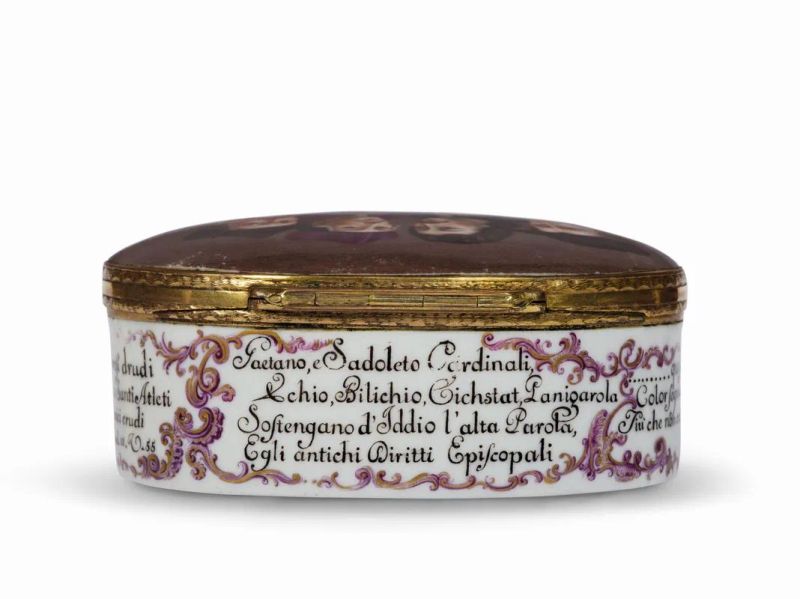

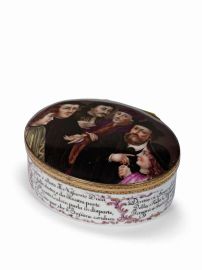

Ginori Manufactory, Doccia

SNUFFBOX KNOWN AS “OF THE HERESIARCHS”, CA. 1760-1765

Polychrome painted porcelain with gilded copper fittings, 4.2x9.4x7.3 cm

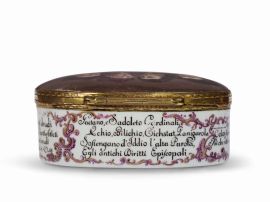

Writ inscribed on the main body (translated): Erasmus is by the side of Duke of Nassau / and on the right, and on the left / of Renata. Calvin talks to one side / and Luther seems to leading the Saxon (front); … Here you see the Heresiarchs / With their followers of each Sect, and with many / more than you think Are the tombs filled / (Dante, Inferno IX, 127) (right side); Gaetano, and Sadoleto, Cardinals / Echio, Billick, Eichstat, Panigarola / May they hold up God’s great Word (back); Within there be the loving priests / of the Christian Faith / Benevolent with their own, ruthless with their enemies / (adapted from Paradise XII, 55) (left side)

The snuffbox, actually called “a veritable box” by Leonardo Gironi Lisci because of its large size (L. Ginori Lisci, La porcellana di Doccia, Milan 1963, p. 53, with reference to a similar piece held today at the Museo Duca di Martina in Naples), presents an elliptic shape entirely painted over in polychrome. The main body of the box is decorated with the above mentioned verses, enshrined and interspersed by thin cartouches traced with a violet monochrome, which refer to the miniatures painted on the lid, identified at the time as follows: on the outside we find the “Princes” of the protestant Reform Erasmus of Rotterdam, John Calvin and Martin Luther together with Jean VI of Nassau [1], John Frederick I of Saxony, and Renata, duchess of Ferrara [2]; on the inside we find the six defenders of the Catholic faith, cardinals Jacopo Sadoleto and Tommaso de Vio, Johannes Mayer, Eberhard Billick, Leonhard Halle [3], and Francesco Panigarola (for the traditional identification of these characters see B. Beaucamp Markowsky, Boites en porcelaine des manufactures europeennes au 18° siècle, Freiburg 1985, pp. 521-522). On the bottom on the snuffbox we find a painting of an enclosed bible, bearing the inscription Bibbia Sacra, radiating rays of light and enshrined within elegant rocaille cartouches.

We have no certain information regarding the identity of who painted this beautiful snuffbox. While in 1963 Leonardo Lisci Ginori suggested Giovacchino Rigacci, leader of the Doccia painters between 1575 and 1771, basing this attribution on an excerpt from a relation by the economist Joannon de St. Laurent (L. Ginori Lisci, op. cit. 1963, p. 142), in 2009 Alessandro Biancalana argued that this attribution might have be erroneous (A. Biancalana, op. cit. 2009, p. 173).

The learned theme of this snuffbox [4], certainly unusual for the luxuries produced by the Doccia manufacture, proved popular nonetheless, so much so in fact that it was repeated in at least two more pieces, one of which is found today at the Museo Duca di Martina in Naples (inv. n. 2836) whilst the other is remembered by Ginori as being held in the collection of Countess Ancillotto in Rome (L. Ginori Lisci, op. cit. 1963, p. 142).

Esposizioni

Lucca e le porcellane della Manifattura Ginori. Commissioni patrizie e ordinativi di corte, Lucca, 28 luglio – 21 ottobre 2001 (n. 193)

Bibliografia

A. Mottola Molfino, L'arte della porcellana in Italia, Milano 1976, tav. LXIII/LXIV;

A. d’Agliano, A. Biancalana, L. Melegati, G. Turchi (a cura di), Lucca e le porcellane della Manifattura Ginori. Commissioni patrizie e ordinativi di corte, cat. della mostra, Lucca 2001, p. 255 n. 193;

A. Biancalana, Porcellane e maioliche a Doccia. La fabbrica dei Marchesi Ginori. I primi cento anni, Firenze 2009, pp. 173-174

Crediamo che nessun gruppo di oggetti della manifattura di Doccia sia stato tanto ignorato quanto le tabacchiere.

Infatti, se scorriamo le numerose pubblicazioni sulla porcellana europea e quelle poche apparse sulla porcellana italiana, noi troviamo illustrate ed attribuite a Doccia soltanto due tabacchiere... mentre la produzione di tabacchiere fu in realtà abbondantissima, e gli esemplari rintracciati presentano una grande varietà di forme e di tipi, ed hanno un notevole pregio.

Possiamo dire che le tabacchiere nacquero con la stessa fabbrica di Doccia. Infatti, già ai primi del 1739, cioè pochi mesi dopo la prima "cotta", con le tazzine, i piattini e i vassoietti, furono prodotte alcune scatole per il tabacco, perché fra le spese figurano quelle relative a "una cerniera d'argento dorato per una tabacchiera di porcellana".

Col tempo, la lavorazione di questi oggetti prese un tale sviluppo, che nel 1741 ne furono prodotte ogni mese a centinaia: il modellatore Pietro Orlandini, nel solo mese di agosto, modellò ben 485 tabacchiere, e nel settembre altre 488. Tali cifre illustrano chiaramente l'importanza di questo settore nella produzione.

Leonardo Ginori Lisci, in La porcellana di Doccia, Milano 1963, p. 51

[1] Given the importance of this piece, we suggest the following observation with regard to the “Nassavio duca”, the “Duke of Nassau”: seeing as Nassau became a Duchy in 1806, after having always been a county, we may understand the word “Duke” in the sense of military leader. In this case, the identity of the figure, looking at the portrait, might correspond to that of William I of Orange (1533-1584), who took part in the Netherlands’ war of independence against the Spanish. We do not think that this figure ought to be identified as being William’s younger brother, John VI of Nassau Dillenburg (1536-1606), who did not hold any relevant military roles.

[2] Renata of Valois-Orleans (1510-1575), princess of France, married to Ercole II of Este and thus duchess of Ferrara, was a strenuous defender of the protestant faith and is rightly inserted amongst the so-called Heresiarcs as she held a very important historical role. Among the many events regarding her life, in 1536 she received an incognito visit by John Calvin, who had already published his Christianae religionis institution in Basel, and with whom Renata would maintain a regular correspondence up until the death of the Genevan reformer. She paid a personal price for her religious choice when her husband had her imprisoned, and she continued to protect the protestant reformers until her death.

[3] In the verses he is named “Eichstat”, probably in reference to the prestigious catholic university of Eichstatt-Ingolstadt, whose most famous rector of the time was Peter Canisius (1524-1597), first German founder of the order of the Jesuits. He was among the staunchest defenders of the Counterreformation and wrote a catechism clearly opposing Luther’s theses. He was proclaimed Doctor of the Church in 1925 and is today celebrated as a saint on the 21st of December. We do not think it plausible to identify “Eichstat” as Leonhard Haller (1500-1570) who lived mainly in Eichstatt but was a character of secondary importance compared to the others, as he was a suffragan bishop of that city and was later sent to the dioceses of the ancient Philadelphia of Araby (today’s Amman). The image of Canisius seems furthermore to fit the portrait on the snuffbox.

[4] It has been noted in the analysis of this piece how even the use of text is the result of thorough research and adaptation. The text incorporates a quote from Dante translated above, and which in the original reads: Erasmo è allato del Nassavio Duca / e dalla destra, e da sinistra parte / a Renata. Calvin parla in disparte / E Luter par che il Sassone conduca (fronte); ... qui son gli Eresiarche / Color seguaci d'ogni Setta, e molto / Più che non credi Son le tombe carche / Inf. IX,127. Dante’s reference is to the heretics of his time, the Epicureans: in this case, the reference is adapted to a contingent situation, and the heretics are the protestant fathers, following the dictates of the Council of Trent. The other verses refer to the defenders of the Faith, in Italian: Gaetano, e Sadoleto Cardinali / Echio, Bilichio, Eichstat, Panigarola / Sostengano di Dio l'alta parola (retro); Dentro vi Sono gli amorosi drudi / Della Fede Cristiana i Santi Atleti / Benigni a suoi, ed a'nemici crudi / adapted from Par. XII, 55. These verses originally referred to the birth of St. Dominic, thought of as a promoter of the Christian faith (“drudo”). All the verses here have been put into the plural so as to match them with the six cited defenders.