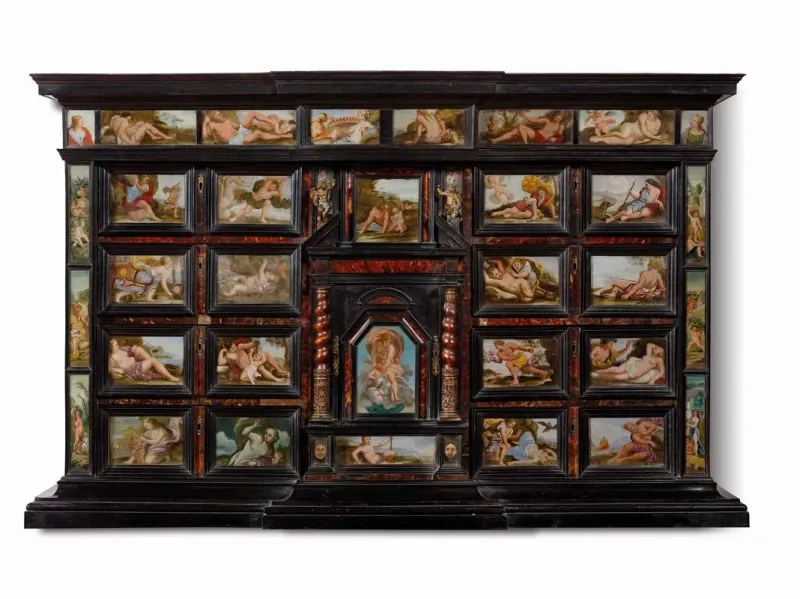

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17TH CENTURY

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17TH CENTURY

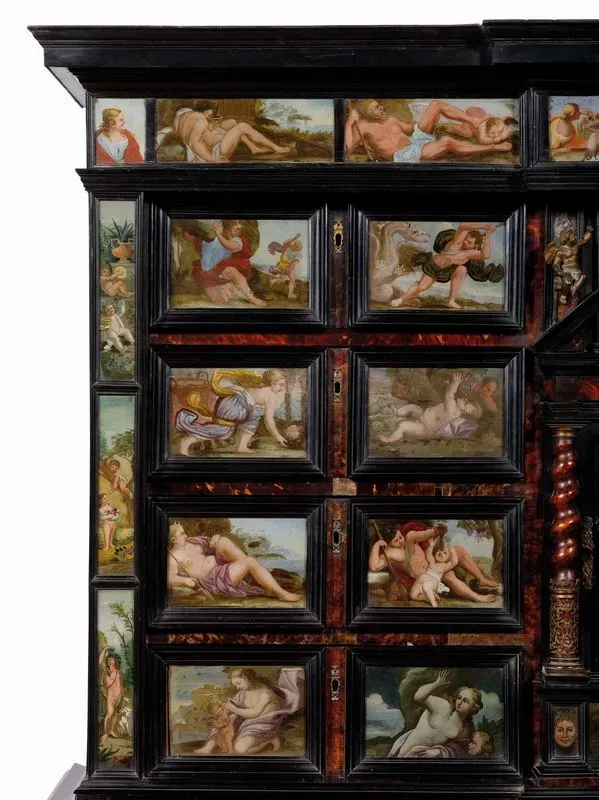

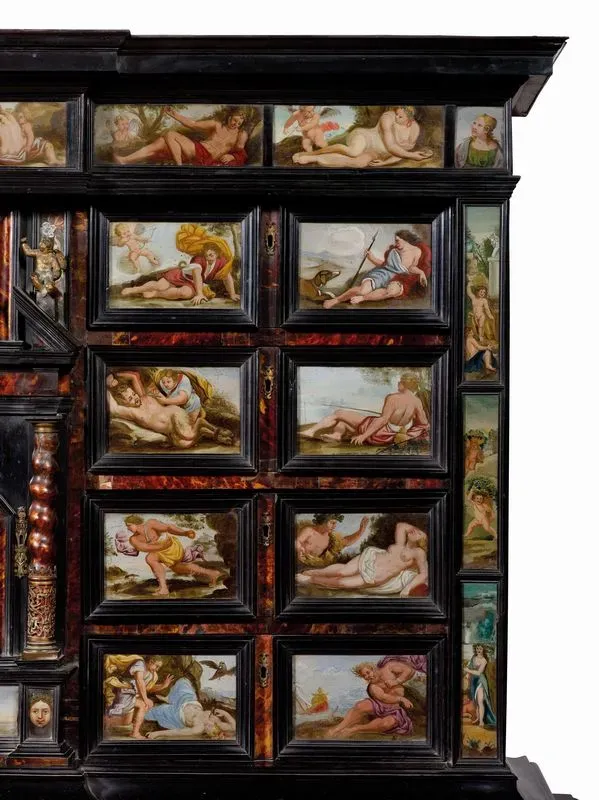

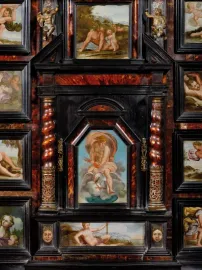

Carved wood, veneered ebony and tortoiseshell with additions of gilded bronze; large, square shape, on a moulded base, centre jutting in front with eight drawers framing an aedicule held up by twisted columns embellished at the base by a traforato motif with gilded bronze racemes. The columns enshrine a portal surmounted by a split gable bearing two winged putti in gilded bronze. The front is adorned with oil-painted glass panes depicting mythological and classical scenes. The piece rests on a sculpted and ebonized wood base, made in a later time. 111.5x178x47.5 cm; base 92x191.5x55 cm

Known since the time of Tutankhamon, in whose tomb numerous examples of cabinets were unearthed in 1922, and having passed through the classical, the cabinet reached western culture after many changes in usage and shape. Its use became widespread in Italy beginning from the 16th century. This piece of furnishing was connected to the birth of the studiolo, or study, a strictly private era of the typical humanist’s residence, where he could retire to dedicate himself to his studies and cultural interests. The study room was soon populated by wondrous collections of art and rare objects, becoming over time a more and more complex space, a small microcosm which could reflect the complexity of the surrounding world. It is in this context, a forerunner to the later Wunderkammer, that the cabinet found its popularity, as a place to store the most precious objects, and thus becoming the par excellence piece of furnishing of any study, refined in its make as much as in its contents.

Over the course of the centuries, in Italy as in the rest of Europe, the cabinet left the enclosed context of the study to become more and more something to be shown off, meuble de parade et d’apparad which ought to express the political and dynastic interests of the rulers of Europe, and often given as a precious gift among them. The most prestigious artists of the time were called upon to create them. These artists could be, depending on which techniques they used, gold- and silversmiths, as well as carvers of precious stones, coral, and ivory, sculptors, painters, bronze-workers. A rich and varied list of materials were used in creating cabinets, always with the intention of making something excellent and truly impressive. At the same time, under the influence of baroque grandeur, the proportions of these furnishings became more and more monumental and imposing, evolving into more and more complex designs – a complexity reflected also in the interiors of the furnishing, where drawers and pockets create miniature palaces alongside a whole series of secret compartments and pulleys.

In the context of this search for the most precious and rare materials, beginning from the 1640s the use of tortoiseshell became more and more frequent. This is a very prized material, capable of creating an effect of great preciousness by shining bright against the black of the ebonized wood, and it used to be easily available in the Spanish colonies. Due to Spanish rule, tortoiseshell veneer spread across Italy, especially in Naples, where it became the distinctive trait of mid-16th century Neapolitan cabinets.

Together with the use of tortoiseshell, through a constant search for refinement and elegance Naples saw the spread of the custom of decorating cabinets with oil-painted glass panes depicting scenes from classic mythology, allegories, and less frequently biblical episodes. The technique of painting on class was especially appreciated by the nobles and rulers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. An example of this is the decision by Ferdinando de’ Medici to include in his collection of paintings some small glass-pane pictures made by Luca Giordano. Numerous documents from the time testify precisely to the way in which the students and followers of the Neapolitan painter Luca Giordano specialized at the time in the decoration of grandiose pieces of furnishing. In 1679, for example, Giovan battista Tara was paid for the realization of “a pair of ebony desks inlaid with a number of paintings on crystal”, whilst Carlo Garofalo, student of Luca Giordano and considered to have been the best painter on glass active in Naples in the second half of the 17th century, was “sent by his master to King Charles II of Spain, where he was summoned to paint the crystals which were to serve to decorate the chests and other adornments of the royal apartments”. And again, Domenico Coscia is mentioned as a painter who “was very able in painting those crystals used for decorating desks”. The list of Neapolitan painters who were disciples of Giordano and who are remembered for their glass paintwork may also be enriched by many more characters, such as Domenico Perrone, Francesco della Torre, Andrea Vincenti.

During the second half of the 17th century, numerous cabinets were created by these successful artistic congeries, in which the best glass painters of the time were able to cooperate with manufactures that were highly specialized in creating greatly complex designs made from precious materials such as tortoiseshell. The piece proposed here is in fact similar to works painted by students of Luca Giordano. Among the most significant examples of this is the cabinet dated from the 1670s and given to the Palazzo Pitti Collection in Florence by Emmy Levy (fig. 1), similar to our piece but even more monumentally proportioned. Other comparisons can be made with the cabinet found the Palazzo Barberini in Rome and with the London Victoria and Albert Museum cabinet (fig. 2) which was acquired by the museum in 1870. Analogous artefacts are furthermore catalogued and described within the inventory documents of the Prince of Avellino and of Cardinal Carafa, both members of the Neapolitan aristocracy.

Comparative literature

A. González-Palacios, Il Tempio del Gusto. Le Arti Decorative in Italia fra Classicismi e Barocco, II, Roma e il Regno delle Due Sicilie, Milan 1984, p. 223;

M. Riccardi Cubitt, Mobili da Collezione. Stipi e Studioli nei secoli, Milan 1993, pp. 10-12 e 87-89

E. Colle, Il Mobile Barocco in Italia, Milan 2000, pp. 66-67;

G. Baffi, Il mobile napoletano nella storia e nell’arredamento, dal 1700 al 1830, Portici 2011, pp. 14-15