Marco Vitruvio Pollione

(70-80 a.C. ca. – dopo il 15 a.C. ca.)

Cesare Cesariano

(1483 – 1543)

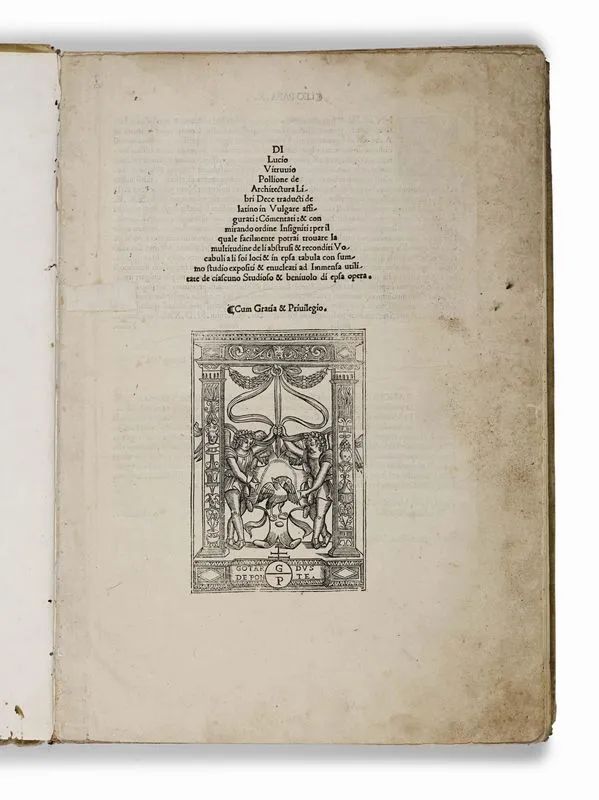

DE ARCHITECTURA LIBRI DECE TRADUCTI DE LATINO IN VULGARE.

(Como, Gottardo da Ponte, 1521).

Provenance

Libreria Carlo Clausen già Ermanno Loescher (grande etichetta azzurra al verso della sguardia anteriore); Sergio Colombi (ex libris figurato al contropiatto anteriore con motto "Perché giammai tedio non provi" e data di acquisto a matita al contropiatto posteriore "15 luglio 1957"); collezione privata.

Literature

Adams V 914. Berlin Katalog 1802. Cicognara 698. Harvard-Mortimer Italian 544. Sander 7696. PMM 26: "the most beautiful of all the early editions".

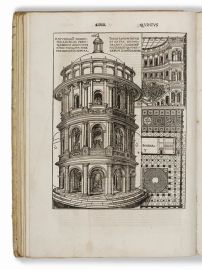

Folio (393 x 280 mm). [iv] CLXXXIII [I] [6] ll. Collation π2 A-Z8 π6. Printer’s device on title-page and on l. Z7v. 117 wood engravings, 10 of them full-page. Numerous large ornate initials. Text enclosed within commentary. Eighteenth-century binding in full vellum over boards with hand-written title on spine. Figured bookplate of Sergio Colombi on inner front cover, label of “Libreria Carlo Clausen già Ermanno Loescher” on verso of front fly. One typewritten and one hand-written card pasted to the recto of front fly and surrounded by minute hand-written notes, another loose hand-written card. Leaves π3-π8 bound at the end of the volume, probably when it received the current binding (originally they were at the beginning); title-page reinforced to outer margin; a few other reinforcements to inner and outer margins, and some minor restoration; quire “D” with a short worm-trail that has been restored on some leaves, with minimal portions of text hand-written to imitate the print; last two ll. restored at the top and with pagination and title hand-written to imitate the print; pale marginal water-stains; occasional marginalia in an old hand. Overall a very good copy, with fresh wood engravings, and with the two famous plates of the Vitruvian Man not censored.

CELEBRATED FIRST EDITION IN ITALIAN, EDITED BY LOMBARD ARCHITECT AND PAINTER CESARE

CESARIANO AND SPLENDIDLY ILLUSTRATED BY HIM WITH 117 WOOD ENGRAVINGS. COPY FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE RENOWNED BIBLIOPHILE AND PHILANTROPIST SERGIO COLOMBI.

Considered as the theoretical foundation of all Western architecture, the De Architectura was written by Vitruvius probably between 35 and 25 BC, in the last few years of a successful career in which he was also the architect and civil engineer of Emperor Augustus – to whom the work is dedicated. Through the ten books thank compose it, Vitruvius expresses concepts that have a universal value and are still valid. He is famous for having said that a building must show the three qualities of firmitate, utilitate, venustate, i.e. to be solid, useful and beautiful, is famous. Vitruvius also defines architecture as a scientific discipline that contains all other forms of knowledge, and he introduces the architect as an expert who must have a knowledge of design, geometry, optics, mathematics, history, philosophy, music, medicine, law, astrology, astronomy.

An essential source for the study of Greek and Roman architecture and the design of large structures

(buildings, aqueducts, baths, ports, etc.) as well as smaller ones (machineries, measuring instruments,

utensils, etc.), the work deals with “the theoretical and practical knowledge acquired in the last two

Hellenistic centuries in the field of architecture and engineering. Vitruvius believes himself to be the

representative and guardian of a long tradition that he thinks has come to the degree of perfection”

[translated from Paolo Clini, http://www.centrostudivitruviani.org/studi/de-architettura/].

The De Architectura is the only classical architectural treatise that has survived intact thanks to a single copy hand-written at the court of Charlemagne at the end of the 8th century, now preserved at the British Library as a Harley Manuscript 2767. Other manuscript copies were made after that (there survive around ninety), but the essay had no influence on medieval architecture. It was rediscovered and acclaimed only from the mid-fifteenth century, thanks to Lorenzo Ghiberti, who drew from it in his Commentarii, and Leon Battista Alberti, who used it as a model for his De re edificatoria. Francesco di Giorgio Martini made a first partial translation into Italian; Raphael commissioned a private translation to collaborator and friend Fabio Calvo. However, both versions remained handwritten.

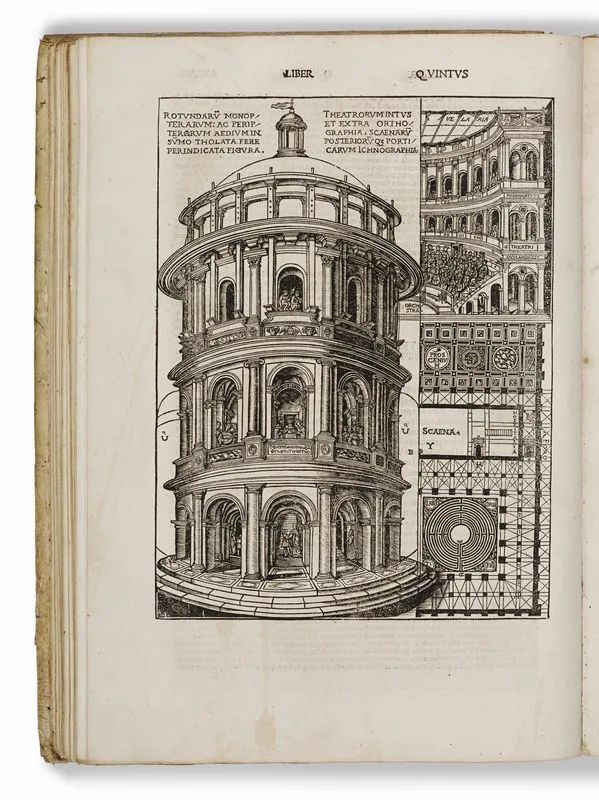

The first print edition of the work saw the light in Rome between 1486 and 1487, published by Eucharius Silber and curated by humanist Giovanni Sulpizio da Veroli. In 1511, there followed the first illustrated edition, issued in Venice by Giovanni Tacuino and curated by Giovanni Giocondo, an architect and engineer from Verona who embellished the Vitruvian text with 136 wood-engraved vignettes. Although fundamental to the understanding of the somehow obscure Latin of Vitruvius, these images are rather elementary and very different from the large and elaborate wood engravings that adorn the present edition, which was translated, commented and illustrated by the Lombard architect, engineer and painter Cesare Cesariano (1483-1543).

The merit of Cesariano is of having made the Vitruvian work accessible to everyone for the first time,

and in particular of having interpreted and depicted its contents with the technical eye of a Lombard

architect influenced by Bramante, and with the vast classical culture of a Renaissance humanist. His

translation and his commentary are an encyclopaedia of the knowledge of the time and offer an overview of its artistic world and society. Cesariano names many artists he has seen and appreciated, including Bramante, whom he defines a “tutor” and a “master” in several passages of the book, and also cites nobles from the Sforza family who loved art and architecture. Most of all, Cesariano applies the rules deduced from Vitruvius to Romanesque and Gothic monuments that he knows well and he reproduces, such as the Milan Cathedral.

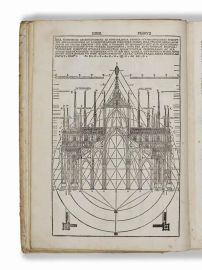

In fact, three of the most important and famous plates of this edition (on leaves XIIII, XV, and XVv), are devoted to the plan, prospective sections and details of the Duomo. These are the first portraits of the Milan Cathedral in a printed book.

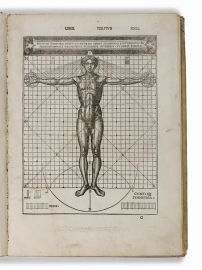

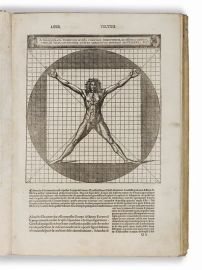

Just as much famous are the two large wood engraving illustrating the ideal proportions of the human

body according to Vitruvius, i.e. the homo ad quadratum and the homo ad circulum (leaves XLIX and

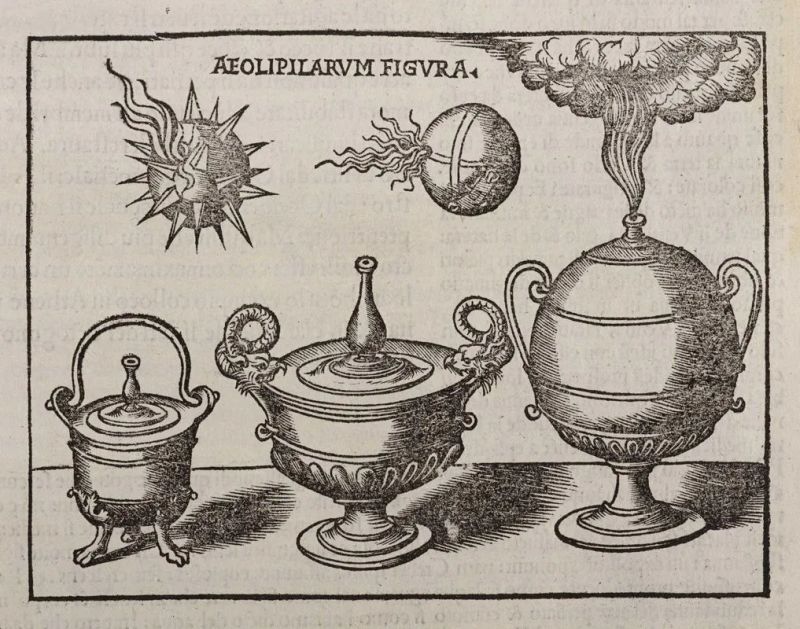

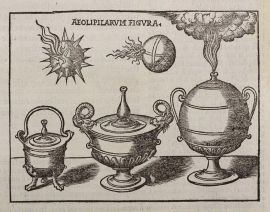

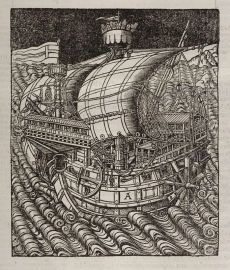

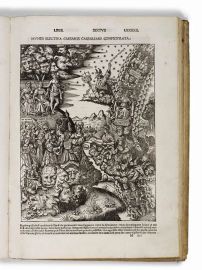

L). Leonardo, in his famous drawing of the Vitruvian Man, had assembled them into a single depictionOverall, the designs of Cesariano, some of which bear his “C.C.” monogram, explain accurately the text by illustrating plants, sections, prospects, details of buildings, measuring instruments, machines and equipment of various kinds. Specifically, we note: the porch of the Caryatids; walls, bastions and towers; various aeolipile models (the steam engine ancestor); the tower and rose of the winds; the discovery of fire and the first human dwellings; Greek bricks and masonry; the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus; a geographical map of Italy; various types of temples and colonnades; the architectural orders; the Basilica Giulia; Greek and Latin theatres and their acoustic systems; thermal baths and gymnasiums; a harbour with hydraulic machines; Greek and Roman houses; construction methods in humid places; furnaces; aqueducts; cement and lime machines; the Pythagorean theorem and the law of Archimedes; armillary and celestial spheres; Zodiacal diagrams; various lifting and displacement equipment; various hydraulic and war machineries.

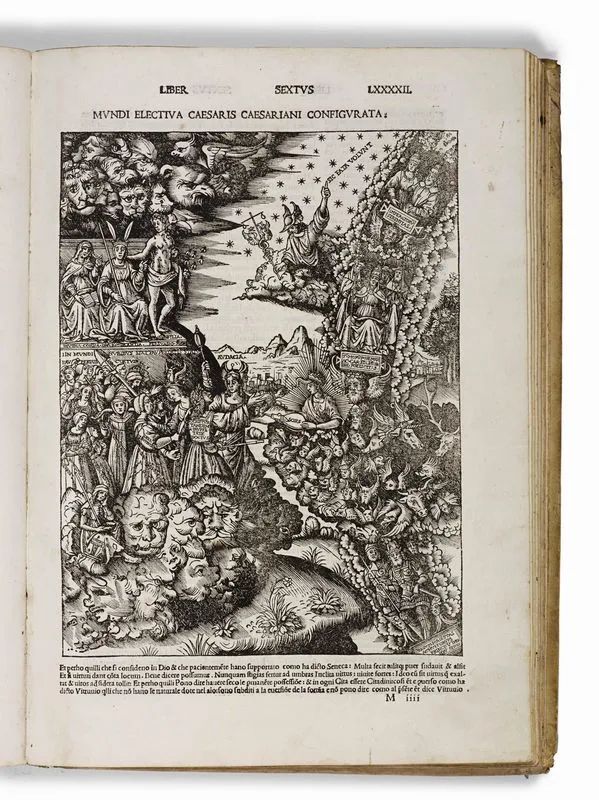

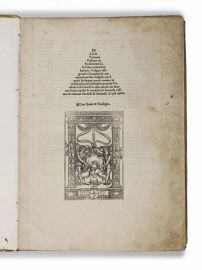

The only wood engraving out of the architectural context is the full page allegorical plate illustrating the pages in which Cesariano tells his life, “perhaps the first figured autobiography of an artist” (see Treccani).

This edition is also particularly relevant because of its complex editorial adventure: at one point, poor Cesariano was even robbed of all his work and even imprisoned. Not having the funds to publish the work, the architect relied on the noble Aloisio Pirovano and on Agostino Gallo from Como, who entrusted the printing to well-known Milanese typographer Gottardo da Ponte and placed by Cesariano’s side the two humanists Benedetto Giovio and Mauro Bono. Everything run smoothly until Book IX, when Cesariano was dismissed, forced to flee, robbed of his manuscript and matrices, and finally imprisoned, while the two sponsors and aides completed the work (1,312 copies were printed), without mentioning the true author of translation, commentary and illustrations, neither on the title page nor on the colophon. The name of Cesariano appears in fact only at the incipit and on the autobiographical pages. The architect filed a lawsuit against his detractors, which he won in 1528. This unfortunate episode did not stop him from seeing his career crowned by the appointment of “Architect of the city of Milan” in 1533. Neither it stopped him to gain an immortal fame thanks to his edition of De Architectura.

This copy belonged to the illustrious Swiss bibliophile Sergio Colombi (1887-1972), great collector of manuscripts, incunabula and precious antiquarian books. Colombi was a dynamic man with variegated interests. The constant advancement of his banking career, which led him over the years to occupying

ever higher offices, was accompanied by an unremitting commitment in the cultural life of Canton Ticino and by the magnificent obsession for the collecting of antique carpets and paintings as well as books.

Sergio Colombi was born in Bellinzona on 27 December 1887. His father Luigi was a lawyer and a prominent figure in Switzerland at the time. Colombi attended the Scuola Cantonale di Commercio, but had to forgo university studies perhaps for economic reasons. In Lugano, where he had moved for work, he met the famous antique bookseller Giuseppe Martini, with whom he began a lasting friendship. Martini enriched the collection of Colombi with numerous incunabula and manuscripts, many of which were then offered by the collector to local and Italian institutions. In 1962, Colombi gave a hundred incunabula to the Biblioteca Cantonale of Lugano, which greatly enhanced its collection of old books. In 1968, two years after the violent flood that had struck Florence in 1966 and severely damaged its book heritage, Colombi gave to the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale the precious Baruffaldi Code, a manuscript of Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata with notes and variants written by the Cardinal Scipione Gonzaga, who was a friend of Tasso’s. Thanks to this this generous donation, a few months later the Italian Ministry of Education awarded Colombi a gold medal. Finally, in January 1975, three years after the death of the illustrious bibliophile on January 13, 1972, his widow, Mrs. Valentina Colombi Bonetti, handed over to the Biblioteca Cantonale of Lugano forty-four Aldines, as her husband had requested.

The present copy features the figured bookplate of Sergio Colombi on the inner front cover, and a number of pencilled annotations on the front fly, as well as a typewritten and hand-written note, both applied to the front fly. Other notes in the same minute handwriting appear on a loose card. They could be attributed to Bianca Colombi, the younger sister of the collector, who helped him when Colombi began to have sight problems. These glosses relate information about this edition and the bibliographic repertoires that record it.