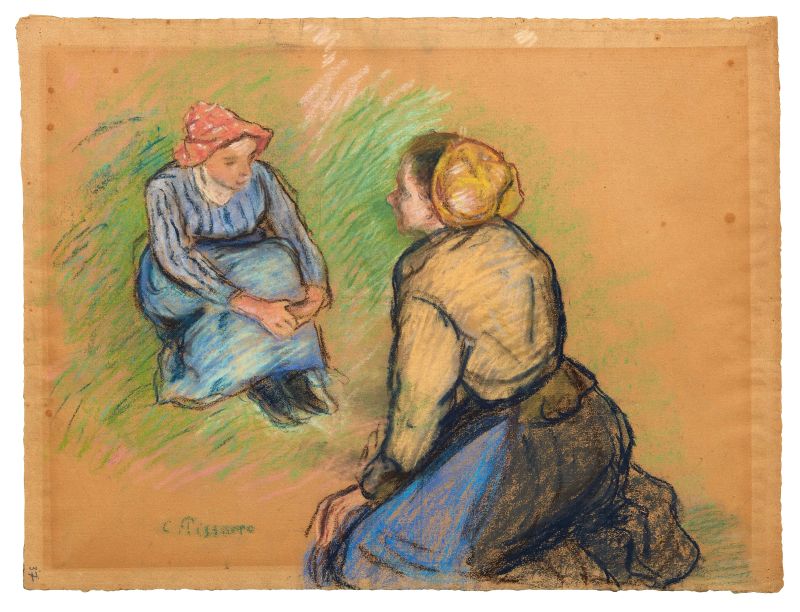

Camille Pissarro (Charlotte amalie, 1830 - Paris, 1903)

Camille Pissarro

Camille Pissarro

(Charlotte Amalie 1830 - Paris 1903)

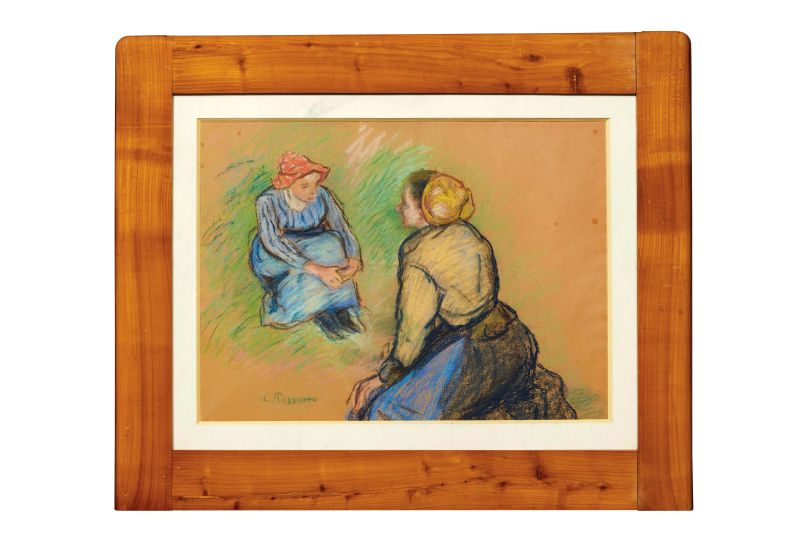

PAYSANNES ASSISES

1880 circa

firmato in basso a sinistra

pastelli su carta

mm 468x615

SEATED PEASANT GIRLS

circa 1880

signed lower left

crayons on paper

18 5/16 by 24 5/16 in

L'opera sarà inclusa nel Pissarro Digital Catalogue Raisonné di prossima pubblicazione, a cura del Wildenstein Plattner Institute.

This work will be included in the forthcoming Pissarro Digital Catalogue Raisonné, being prepared under the sponsorship of the Wildenstein Plattner Institute.

L'opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Provenienza

Collezione Erna Stiebel

Christie’s, New York, Impressionist and Modern Paintings – Drawings and Sculptures, 11 maggio

1995, lotto 231 (dalla proprietà di Erna Stiebel)

Trento, Paolo Dal Bosco

A partire dal 1873, Pisarro si trasferisce nella Val-d’Oise, lavorando tra Pontoise, Osny ed Auvers. Dal 1880, e fino alla sua morte, resta poi a Eragny, nel nordovest parigino, interessandosi ai motivi della vita rurale, ai contadini, i quali, nelle opere successive al 1881, sono ritratti nei loro umili ambienti d’appartenenza, una scelta dovuta, in parte, al credo politico dichiaratamente anarchico del pittore francese. A differenza di Millet, infatti, Pissarro non conferisce alcuna vena sentimentale ai suoi contadini, anzi, in essi troviamo espressa la sua opposizione nei confronti dell’aura romantica che generalmente li circondava. In quanto esseri semplici, secondo Pissarro, questi erano da presentare senza sentimentalismi, nei loro atteggiamenti un po’ goffi e talvolta sgraziati. Mosso da un genuino interesse nei confronti delle loro fatiche quotidiane piuttosto che da un immaginario di tipo letterario, poetico, simbolista, scelse dunque di non renderli attraenti o affascinanti, ma di ritrarli nel loro vero aspetto, nei loro abiti, intenti alle loro occupazioni. A margine della settima mostra impressionista del 1882, dove fu esposta una serie significativa di questi suoi soggetti, Huysmans sottolineò come l’artista si fosse finalmente liberato dal ricordo di Millet, dipingendo «la gente di campagna senza falsa grandezza, semplicemente come egli la vede» (L’art moderne, Appendice, Paris 1883). Il tema delle contadine sedute, nello specifico, trova ampio spazio nella produzione di Pissarro degli anni Ottanta. Nella nostra composizione non troviamo alcuna traccia di enfasi, le due contadine, riprese in atteggiamenti e gestualità di grande naturalezza, sono infatti in un momento di pausa, in posizione di riposo e di spensierato dialogo. La prima, di spalle, è inginocchiata; l’altra, più lontana in secondo piano, ad aumentare il senso di profondità della scena, è seduta con le mani incrociate dinanzi le ginocchia. Straordinaria è la plasticità e la solida volumetria con cui Pissarro rende le loro fisionomie, soffermandosi con sicurezza, ad esempio, sul volto di profilo del personaggio di spalle. L’uso del pastello, derivato dalla grande ammirazione da lui nutrita negli anni Ottanta per Degas, supporta l’artista in una definizione più netta, rapida e dinamica dei loro indumenti, indagati nelle loro trame, nella loro materialità, riuscendo a conferire, al tempo stesso, particolare vivacità e brillantezza alle cromie dei tessuti.

In 1873, Pissarro moved to the Val-d’Oise, working in Pontoise, Osny and Auvers, and from 1880 until his death remained at Eragny, in the north-western suburbs of Paris. He painted views of rural life and farmers, who in the post-1881 works are portrayed only in their humble surroundings; his decision to do so was motivated in part by his declaredly anarchistic political credo. Differently from Jean-François Millet, Pissarro did not infuse his farmers with any trace of sentimentality; quite the opposite, in fact. They express his opposition to the Romantic aura with which such subjects were generally surrounded. As simple folk, according to Pissarro, they were to be presented without sentimentalism, in all their somewhat awkward and sometimes bumbling comportment. Moved by a genuine interest in their daily labours rather than by a literary, poetic or symbolic image, he chose not to render his subjects attractive or fascinating but rather to paint them as they were, with their real expressions and their real clothing, intent on real tasks. After the seventh Impressionist exhibition of 1882, which showed a significative series of these of Camille Pissarro’s compositions, J. K. Huysmans pointed out that the artist «has entirely detached himself from Jean-François Millet’s memory [and] paints his country people without false grandeur, simply as he sees them» (L’art moderne, Appendice. Paris 1883). We find no trace of emphasis in his portrayals of seated peasant women, oft-recurring subjects in his production of the Eighties. In our composition, two seated peasant women, whose poses and gestures are entirely natural and relaxed, are taking a moment to rest and chatter. One, her back to us, is kneeling; the other, farther back from the viewer to increase the sense of depth, is sitting with her hands linked around her shins. Pissarro renders their faces with extraordinary plasticity and solid command of volumes, pausing confidently, for example, on the profiled face of the woman we see from the back. His use of pastels, which he took up in the Eighties out of his great admiration for Edgar Degas’ work, supports his clean, quick, dynamic definition and investigation of the weaves and materiality of his subjects’ clothing and at the same time confers a special vibrancy and brightness to the colours of the fabrics.