Claude Monet

(Paris 1840 - Giverny 1926)

FALAISE DU PETIT AILLY À VARENGEVILLE

1896-1897

firmato e datato successivamente “82” in basso a sinistra

olio su tela

cm 65x92

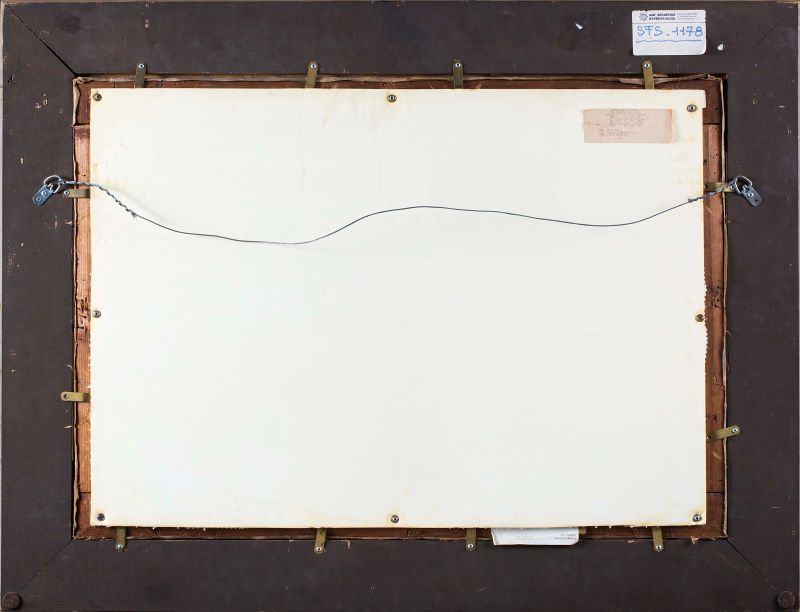

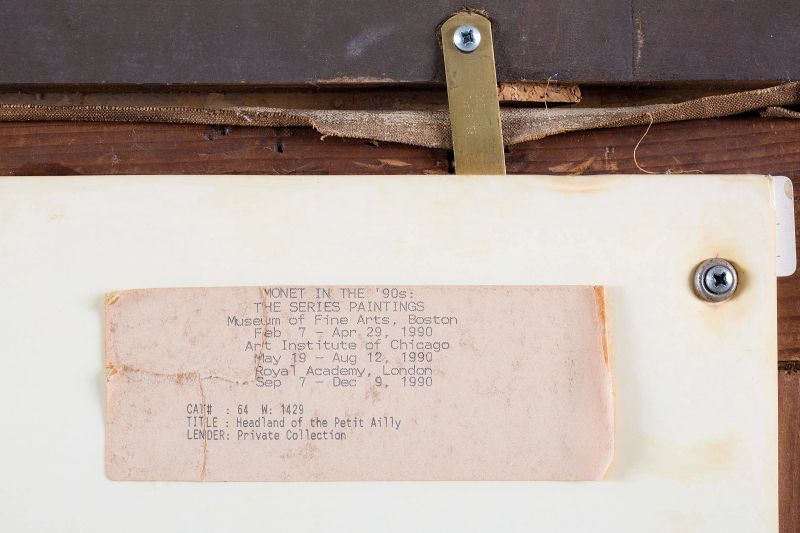

sul retro: etichetta della mostra Monet in the ‘90s, etichetta della Philippe Daverio Gallery Ltd. di New York sul telaio

FALAISE DU PETIT AILLY À VARENGEVILLE

1896-1897

later signed and dated “82” lower right

oil on canvas

25 9/16 by 36 ¼ in

on the reverse: label of the exhibition Monet in the ‘90s, label of the Philippe Daverio Gallery Ltd. of New York on the stretcher

Provenienza

Paul Durand-Ruel e Bernheim-Jeune, acquistato dall’artista, maggio 1920

Collezione Durand-Ruel, 1922

Hotel Drouot, Paris, 10 maggio 1950, lotto 116

Paris, collezione Katia Granoff, 1972 circa

Hotel Drouot, Paris, 16 novembre 1981, lotto 8

Finarte, Milano, 12 novembre 1985, lotto 91

New York, Philippe Daverio Gallery Ltd.

Esposizioni

Monet in the ‘90s: the series paintings, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 7 febbraio – 29 aprile 1990; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 19 maggio – 12 agosto 1990; Royal Academy, London, 7 settembre – 9 dicembre 1990.

Un Monet in Pilotta. La Falaise du Petit Ailly à Varegenville e le origini dell’Astrattismo, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale, Parma, 15 giugno – 28 agosto 2019.

Bibliografia

L. Venturi, Les Archives de l’impressionisme, Paris – New York 1939, vol. I, p. 456.

Monet in the ‘90s: the series paintings, catalogo della mostra (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 7 febbraio – 29 aprile 1990; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 19 maggio – 12 agosto 1990; Royal Academy, London, 7 settembre – 9 dicembre 1990) a cura di P.H. Tucker, New Haven 1989, p. 211, tav. 78.

D. Wildenstein, Claude Monet. Biographie et catalogue raisonné, Lausanne-Paris 1974-1991: 1979, vol. II, p. 294, n. 107; 1979, vol. III, pp. 196- 197, n. 1429, p. 291 lett. 1342; 1985, vol. IV, p. 405, lett. 2345; 1991, vol. V, p. 50, n. 1429.

D. Wildenstein, Monet. Catalogue raisonné, vol. III, Koln 1996, pp. 592-593, tav. 1429.

Una grande parete rocciosa emerge imponente in primo piano bloccando in parte l’estendersi del mare e del cielo. Nella incombenza massiccia della falesia dalle tonalità cangianti, un profilo rosso nella parte inferiore del dipinto tratteggia il perimetro di una piccola costruzione. È il tetto della casetta dei doganieri, usata successivamente come riparo dai pescatori e più volte dipinta da Claude Monet nelle passeggiate a Varengeville, lungo le alte scogliere della Normandia. Una passione, quella dell’artista impressionista, per questi scorci mozzafiato a strapiombo sul mare impetuoso del nord, che comincia nel 1868, quando il ventottenne passa l’inverno a Etretat dipingendo La porte d’Aval, una delle meraviglie naturali del mondo, mentre l’amico Courbet realizza la celebre serie delle onde. Vedendoli lavorare all’aria aperta, Maupassant li sostiene e li definisce ≪coloro che perseguono la verità fino a qui inosservata≫. Vi ritorna nel 1880 e per alcuni anni, ormai sono luoghi che gli appartengono, attrattiva di una certa mondanità grazie agli stabilimenti balneari di Etretat. Suo fratello Leon lo ospita nella casa di Le Petites-Dalles, nei dintorni di Fecamp. Dipinge svariate versioni di queste scogliere, molto apprezzate dal mercato, tanto che il gallerista Durand-Ruel gliene compra più di un centinaio. Nel 1882 ne produce una serie ambientata a Varengeville, poi ripresa tra il 1896 e il 1897 quando vi fa ritorno, mosso da una certa nostalgia per i luoghi in cui aveva lavorato in passato. Risale ad allora la lettera a Durand-Ruel: ≪J’avais besoin de revoir la mer et suis enchante de revoir tant de choses que j’ai faites il y a quinze annees≫ (Wildenstein, prima edizione, vol. III, lettera n. 1324). Giocando con un mutamento costante delle condizioni atmosferiche e quindi di luce, egli mantiene una certa distanza tra il suo sguardo e le incombenti pareti rocciose affacciate su un mare che occupa il primo piano del quadro. Protagonisti sempre gli stessi elementi naturali, dove il mare agitato o tranquillo, sorgente sempre nuova di energia, a volte è raffigurato assieme a lembi di spiaggia popolata da persone o da piccole imbarcazioni, tra sole, nebbia, vento. Nel caso di questo dipinto, il primo piano del mare viene occupato quasi interamente dalla falesia che sbarra la visuale in un punto panoramico dove la costa termina bruscamente con dirupi e voragini. Mare e cielo s’incontrano lungo una linea orizzontale ben netta, la profondità viene data dalle tonalità chiare e scure che segnano le irregolarità della roccia e dalla gradazione di azzurri marini. La calda gamma di colori utilizzata da Monet e uno degli elementi che ha spinto Daniel Wildenstein a collocare il dipinto, benché datato 1882, al 1896-97. Non è l’unico caso di errata datazione effettuata dall’artista a posteriori, in questo caso Monet aveva ottant’anni, e quindi comprensibile che si sia confuso sul periodo di esecuzione. La conferma ce la offre una lettera che il pittore invia a Joseph Durand-Ruel, figlio del noto mercante Paul, il 26 aprile 1920, durante i preparativi di una mostra presso la galleria parigina dove il nostro quadro verrà esposto il mese seguente: ≪Cher Monsier Joseph, les tableaux que vous avez choisis sont tous signes, par consequent prets a vous etre livres≫.

An imposing rocky wall takes up the foreground, partially blocking the view of the sea and sky. At the bottom of the painting, amidst the brilliant colours of the massive cliff, is a small structure outlined in red. It is the roof of the customs officers’ house that fishermen later used as a shelter; Claude Monet painted it several times during his walks along the high cliffs of Normandy at Varengeville. The Impressionist artist’s passion for these breathtaking views of the stormy northern seas began in 1868 when the twenty-eight year old Monet spent the winter at Etretat painting La porte d’Aval, one of the natural wonders of the world, while his friend Gustave Courbet was working on his famous seascapes known as The Waves. Seeing them working outdoors, Guy de Maupassant supported them and called them «those who pursue truth that had not been seen up to now». Monet returned there in 1880 and for some years the places became his, attracted as he was by the sophisticated atmospheres of the bathing establishments at Etretat. He stayed with his brother Léon in the house at Le Petites-Dalles, near Fécamp. He painted many versions of these cliffs that were greatly admired by the market to the point that the gallery owner Durand-Ruel purchased more than one hundred from him. In 1882, he painted a series set at Varengeville, and then again between 1896 and 1897 when he returned, driven by nostalgia for places where he had worked in the past. His letter to Durand- Ruel dates from that time: «J’avais besoin de revoir la mer et suis enchante de revoir tant de choses que j’ai faites il y a quinze annees» (Wildenstein, first edition, vol. III, letter n. 1324). Working with the constant changes in weather and therefore light, he maintained a certain distance between his gaze and the looming cliffs overlooking a sea that takes up the painting’s foreground. And, the key subjects were always the same natural elements, where the sea – stormy or calm – yet always a new source of energy is depicted with strips of beach populated with figures or small boats, amidst sun, mist and wind. In this painting, the foreground of the sea is taken up almost entirely by the cliff that blocks the view in a panoramic point where the coastline abruptly ends in rocky crags and chasms. Sea and sky meet along a sharp horizontal line, depth is created by the light and dark colours that define the unevenness of the rocks and the blue tones of the sea. Monet’s warm palette is one of the factors that prompted Daniel Wildenstein to date the painting around 1896-97 even though the date on it is 1882. This is not the only instance of an incorrect dating inscribed by the artist at a later time: in this case Monet was eighty-eight years old and we can understand that he was confused about when he had painted it. This is confirmed by a letter he wrote to Joseph Durand-Ruel, son of the renowned art merchant Paul, on 26 April 1920, when he was preparing an exhibition for the Paris gallery where our painting would be shown the following month: «Cher Monsieur Joseph, les tableaux que vous avez choisis sont tous signes, par consequent prets a vous etre livres».