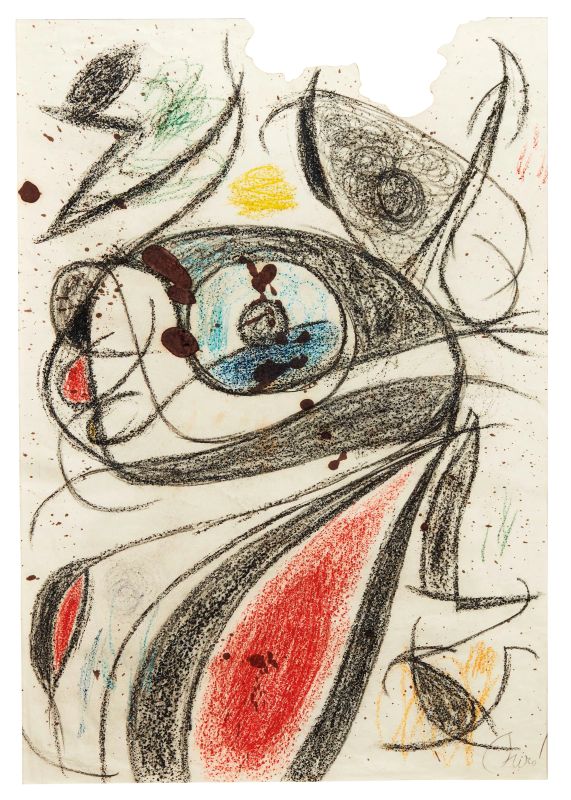

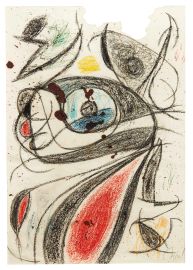

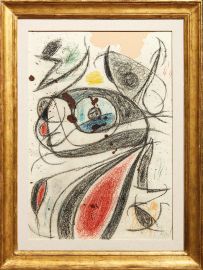

Joan Miró i Ferrà

(Barcelona 1893 - Palma de Mallorca 1983)

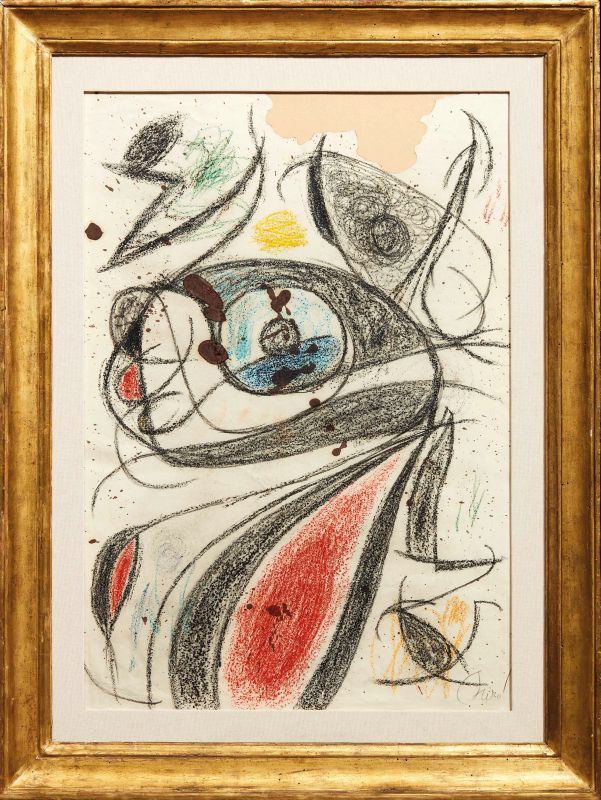

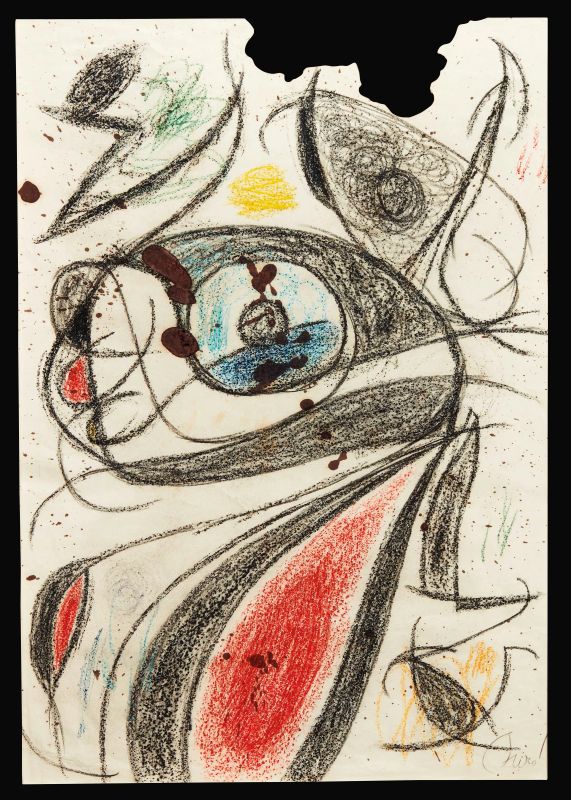

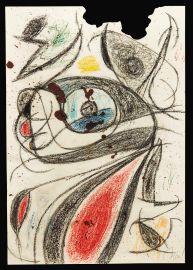

FEMME, OISEAUX

1975

firmato in basso a destra

pastelli colorati e inchiostro su carta giapponese

mm 800x560

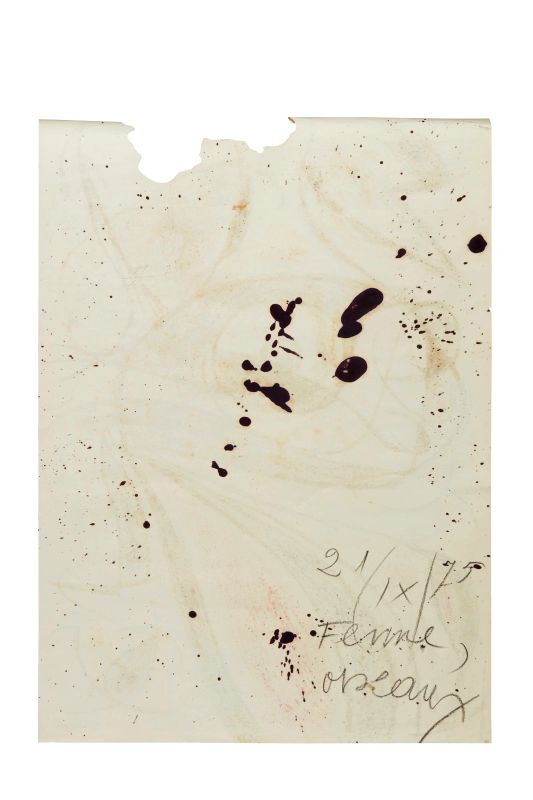

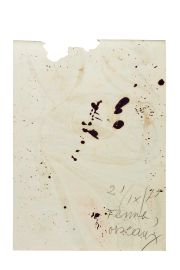

sul retro: datato “21/IX/75” e titolato

FEMME, OISEAUX

1975

signed lower right

coloured crayons and ink on Japanese paper

31 ½ by 22 in

on the reverse: dated “21/IX/75” and titled

L’opera è accompagnata da certificato di autenticità rilasciato dalla ADOM (Association pour la Defense de l’Oeuvre de Joan Miró) il 25 giugno 2019.

This work is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity issued by ADOM (Association pour la Défense de l’Oeuvre de Joan Miró) on 25th June 2019.

L’opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Il linguaggio surrealista di Joan Miró acquisisce la sua maturità, riconosciuta a livello internazionale in Europa e in America, negli anni Quaranta con la serie delle Costellazioni, in cui figura umana, natura, cosmo e mondo animale presiedono alla nascita di un alfabeto onirico. Nei soggetti delle sue creazioni vengono raccogliendosi densi nuclei di forme che scaturiscono dalla meditazione di soggetti archetipici, che vengono sottoposti dall’artista alle più mutevoli trasformazioni. Una caleidoscopica metamorfosi lega insieme infatti gli elementi appartenenti a questi diversi livelli o stadi dell’essere, cui l’artista dà volto e figura, inseguendo e meditando le proprie pulsioni. Su tali fantasmagorie inciderà la fascinazione esercitata dalla visione delle pitture preistoriche sulle pareti delle grotte di Altamira, che dovette rafforzare Miró nella convinzione di poter coltivare in sé la crescita e la proliferazione di segni primitivi, adeguati per misurarsi con una forza primigenia – l’origine – cui ogni sua immagine si riferisce. La donna, dunque, è tema centrale: essa è fertilità, pulsione sessuale, organo riproduttivo, terra, matrice. L’uccello è l’elemento d’aria, traiettoria in movimento, energia, fallo, desiderio, violenza, slancio e contatto con il cielo. Per citare solo alcune occorrenze di questo soggetto ancipite nell’opera dell’artista catalano, ricorderemo Donna circondata da un volo d’uccello, del 1941, o Donna, uccello al chiaro di luna del 1949, olio su tela, Londra, Tate Gallery, dalla serie Donne e uccelli; e poi, ancora, la Donna e uccello del 1964, olio su tela, a Saint Paul de Vence presso la Fondation Marguerite et Aimé Maeght; e, infine, la scultura monumentale Donna e uccello, in cemento e ceramica, realizzata in collaborazione con J. L. Artigas, nel 1982, Barcellona, nel Parco Joan Miró, che insieme alla nostra opera pare appartenere ad una simile famiglia formale, pur nella singolarità delle due diverse realizzazioni. Nella grande opera monumentale, alta circa ventidue metri, si apre infatti entro il corpo eretto della scultura, di evidente richiamo fallico, una forma cava, il cui profilo evoca il sesso femminile. La scultura nasce come gigantesca creatura fittile, come sviluppo di un abnorme progetto vascolare-ceramico, ideato grazie ai decenni di sperimentazione ceramica da parte di Miró. Nel dipinto in esame ritroveremo le stesse forme ovoidali e arrotondate che nello slancio della scultura di Barcellona si innalzano sino a toccare il cielo con la semiluna apicale. Il nostro Femme, oiseaux appare come la proiezione piana di quel mondo di forme globulari e in gestazione, in cui si aprono occhi ipnotici su una rossa forma oblunga, simile al sesso femminile. In una intervista, così l’artista descriveva come avesse coltivato la fioritura delle sue visioni: ≪ Vedo il mio studio come un orto. Per far venire su i frutti, bisogna tagliare le foglie. A un dato momento bisogna potare. Lavoro come un giardiniere o un vignaiuolo. Le cose vengono lentamente. Il mio vocabolario di forme, per esempio, non l’ho scoperto tutto in una volta; si è formato quasi a mia insaputa. Le cose seguono il loro corso naturale. Crescono, maturano. Bisogna innestare. Bisogna irrigare≫. E riconosceva come alcuni soggetti, proprio come quelli della donna e dell’uccello, fossero ≪ temi che non mi abbandonano mai, che ritornano […] li accumulo, come se fossero semi. Alcuni germogliano, altri no≫. (Miró, 1959)

Joan Miró’s surrealistic language came to its maturity and was recognised in Europe and in the U.S. in the 1940s, with the series entitled Constellations, in which the human figure, nature, the cosmos and the animal world preside at the emergence of an oneiric alphabet. Dense nuclei of forms, outflowing from meditation on archetypal subjects, coaxed by the artist to undergo the most diverse transformations, form the centres of his creations. A kaleidoscopic metamorphosis ties together the elements belonging to these diverse levels, or stages, of being, to which the artist gives faces and figures, following and meditating on his own impulses. These phantasmagories are influenced by the fascinating prehistoric Altamira cave paintings, which, when viewed by Miró must have strengthened his resolution to cultivate within himself and in his works a growth and proliferation of primitive signs adequate to confront that incredibly ancient force – the origin – to which every single one of his images refers. Woman, therefore, is the central theme: woman is fertility, the sexual impulse, reproductive organ, earth, matrix. The bird is the element air, a trajectory in movement, energy, the phallus, desire, violence, eruption and contact with the heavens. To cite just a few of this two-sided subject in the works of the Catalan artist, let us recall Woman Encircled by the Flight of a Bird (1941) or Women and Bird in the Moonlight (1949), both oils on canvas (London, Tate) from the series Women and Birds; Woman and Bird (1964), oil on canvas, in Saint- Paul-de-Vence at the Fondation Marguerite et Aimé Maeght; and, finally, the monumental sculpture entitled Woman and Bird, in concrete and ceramic, constructed in collaboration with J. L. Artigas in 1982, in Barcelona’s Parc de Joan Miró, which would seem belong to the same formal family as our work, however singular the two expressions may be. In the large monumental work, about twenty-two metres in height, the erect body of the sculpture with its evident phallic references is split by a vulva-shaped hollow. The sculpture was born as a gigantic fictile creature, as the flowering of an aberrant vascular-ceramic project, conceivable only thanks to Miró’s decades of experimentation with the medium. In our painting, we find the same ovoid and rounded forms which, in the soaring Barcelona sculpture, rise to touch the sky with a crescent moon. Our Femme, oiseaux is, apparently, a plane projection of that world of gestating globular forms in which hypnotic eyes open on an oblong red form similar, again, to the vulva. In an interview, the artist described how he would have cultivated the flowering of his visions: «I think of my studio as a vegetable garden… The leaves have to be cut so the vegetables can grow. At a certain moment, you must prune. I work like a gardener or a wine grower. Everything takes time. My vocabulary of forms, for example, did not come to me all at once. It formulated itself almost in spite of me. Things follow their natural course. They grow, they ripen. You have to graft. You have to water…». And he acknowledged that certain subjects, like woman, like the bird, would never abandon him, but would return; and that he would accumulate them, as though they were seeds, some of which would germinate, others which would not. (Miró, 1959)