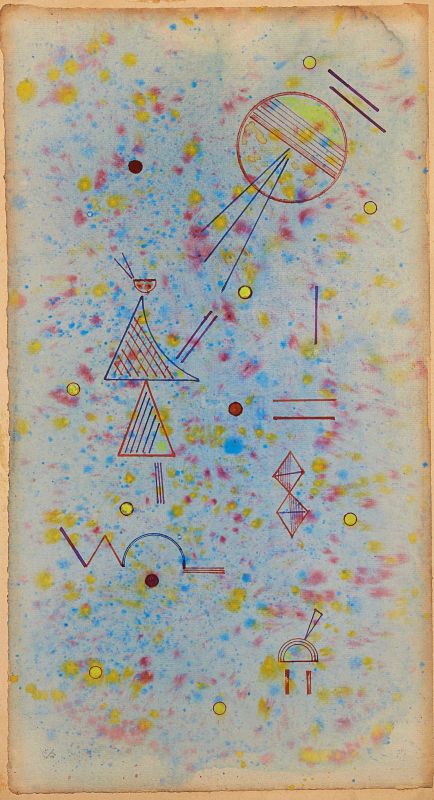

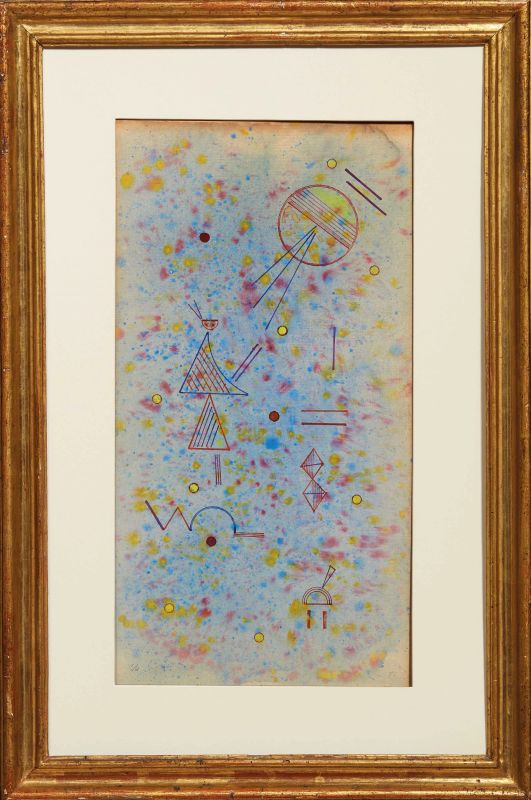

Vassily Kandinsky (Mosca, 1866 - Neully-sur-seine, 1944)

Vassilly Kandinsky

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

DÜNN UND FLECKIG SOUPLE

1931

siglato e datato “31” in basso a sinistra

chine colorate e aniline su carta preparata ad acquerello azzurro applicata su cartoncino

mm 477x259

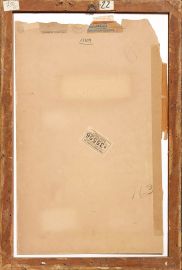

sul retro: timbro della Douane Centrale di Paris, etichetta della mostra Il cavaliere azzurro, etichetta della casa d’aste Digard Maison de Ventes Volontaires

DÜNN UND FLECKIG SOUPLE

1931

signed with initials and dated “31” lower left

coloured ink and aniline on paper prepared with light blue watercolour laid down on cardboard

18 11/16 by 10 3/16 in

on the reverse: stamp of the Douane Centrale of Paris, label of the exhibition Il cavaliere azzurro, label of the auction house Digard Maison de Ventes Volontaires

L’opera è corredata di attestato di libera circolazione.

An export license is available for this lot.

Provenienza

Collezione Gualtieri di San Lazzaro – Riccardo Jucker, 1971

Finarte, Milano, 24 marzo 1988, lotto 372

Collezione privata

Christie’s, London, Impressionist and Modern Watercolours and Drawings, 4 aprile 1989, lotto 372 (con titolo Dunn mid Heckig)

Digard Maison de Ventes Volontaires, Paris, Tableaux modernes et contemporains – Sculptures– Photographies, 7 giugno 2006, lotto 98

Esposizioni

Kandinsky: toiles récentes, aquarelles, graphiques de 1910 à 1935, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, 3 – 29 dicembre 1936.

Efter-Wxpressionisme, Abstrakt Kunst, Neoplasticisme, Surrealisme, Liniens Samenslutning, Kobenhavn, 1 – 13 settembre 1937, n. 41.

Wasily Kandinsky, Guggenheim – Jeune, London, 17 febbraio – 12 marzo 1938.

Janis Kandinsky, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, 21 novembre – 24 dicembre 1949.

Il cavaliere azzurro – Der Blaue Reiter, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Torino, 18 marzo – 9 maggio 1971.

Bibliografia

Il cavaliere azzurro – Der Blaue Reiter, catalogo della mostra (Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Torino, 18 marzo – 9 maggio 1971) a cura di L. Carluccio, Torino 1971, p. 200.

V. Endicott Barnett, Kandinsky watercolours, catalogue raisonné. II. 1922-1944, London 1994, p. 298, n. 1012.

Per undici anni, tra il 1922 e il 1933, Kandinsky insegnò in Germania presso la scuola del Bauhaus di Walter Gropius. In questo lungo periodo al Bauhaus andò concentrandosi con sistematico rigore su una prospettiva di studio e analisi della percezione visiva e più estesamente psicologica e sensoriale, e della disciplina della pittura. La sua sarà una teoria generale della composizione, in cui vorrà studiare gli elementi fondamentali di linea, colore e forma, considerati in se stessi e nelle loro relazioni elementari, sganciati da finalità rappresentative o simboliche, in una grammatica di regole fondamentali per gli elementi formali della pittura pura. Nell’introduzione al catalogo di una mostra tenutasi a Berlino nel 1932 Kandinsky affermava: «Non vorrei passare per un “simbolista”, per un “romantico”, per un “costruttivista”. Mi accontenterei che lo spettatore sentisse in sé la vita interiore delle forze vive adoperate, nella loro relazione […] Chi si accontenta della forma rimane in superficie». Come sottolineava Giulio Carlo Argan, pur elaborando una riflessione e un sistema teorico sugli elementi primari della composizione pittorica, punto, linea, piano, Kandinsky non si proponeva di «partire dalla geometria», ma di giungervi, poiché «la geometria non era un ordine dato a priori ma una chiarezza percettiva che si dava solo al termine del processo». Dunn und fleckig Souple, venne realizzato da Kandinsky nel giugno 1931. Il suo titolo, che si potrebbe tradurre con “Sottile e macchiato flessibile”, si riferisce al congegno compositivo attivato: segni e figure geometriche sono l’impronta visibile di tensioni e di forze, di pesi che qualificano lo spazio percepito e pensato. Analizziamo le sue componenti: il piano macchiato attraverso la tecnica a spruzzo che Kandinsky impiega guardando alle opere dell’amico Paul Klee; la composizione priva di un centro e la disposizione aperta di elementi geometrici, quasi dei geroglifici, che vibrano sonori sul piano in una configurazione “eccentrica”, sottile e flessibile. La trasparenza dei colori, resa più intensa attraverso la tecnica a spruzzo, conferisce all’opera una vibrazione cromatica e luminosa che evoca uno spazio illimitato, una profondità che sottrae alla carta il suo sordo limite bidimensionale. La nozione di “infinito” spaziale, sarà al centro di una lezione presso il Bauhaus nel 1932, in cui Kandinsky descrive le “relazioni a distanza nella pittura” portando l’attenzione degli studenti su quello che egli definisce “ordinamento cosmico”. Prenderà quindi a modello la struttura aperta di un sistema stellare, in cui evidenzierà la presenza di “gruppi”, di “materia nebulare” assimilata a dei “punti in una massa colorata”; e ancora la presenza di “masse limitate di maggiori dimensioni”, e di “bande che si estendono fra le stelle”, insieme a dei “piccoli ammassi globulari” (W. Kandinsky, Tutti gli scritti, a cura di P. Sers, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1973, p. 293). Sembra di star osservando il movimento di espansione formale e cromatica tra le macchie di blu e di giallo – elementi di colore percepiti da Kandinsky in perenne separazione tra loro – dello sfondo della nostra opera, e di avvertire le tensioni tra gli elementi lineari, il loro contrappunto agile, flessibile, sonoro, vivace.

For eleven years, from 1922 to 1933, Kandinsky taught in Germany at Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus school. In this long period spent at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky concentrated with systematic rigour on study and analysis of visual – and, in a wider sense, psychological and sensorial – perception and of the discipline of painting. His was a general theory of composition extending to the fundamental elements of pictorial expression – line, colour and form – considered separately and in their elementary relationships, uncoupled from representative or symbolic ends, in a grammar of basic rules for managing the formal elements of pure, abstract, painting. In the introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition held in Berlin in 1932, Kandinsky stated that he did not want to pass for a “Symbolist” or for a “Romantic” or for a “Constructivist”; that he would be content were the spectator to feel stirring within himself the living force of the relations among the parts. And he concluded that those who settle for form never penetrate the surface. As Giulio Carlo Argan noted, while Kandinsky worked out a theoretical system of the primary elements – point, line, plane – of pictorial composition, he did not propose to start from geometry but to arrive there, because he did not consider geometry to be an order imposed a priori but rather a clarity of perception which emerged only at the end of the process. Dunn und fleckig Souple was produced by Kandinsky in June of 1931. The title, which could be translated as “thin and speckled flexible”, refers to the painting’s active compositive device: signs and geometric figures are the visible prints of tensions and forces, of weights that qualify perceived and contemplated space. Let us analyse its components: the plane, speckled using the “spray” technique he shared with his friend Paul Klee; the composition devoid of a centre; and the open arrangement of the geometric elements, almost hieroglyphics, which vibrate, full-toned, on the plane in an “eccentric”, diluted and flexible configuration. The transparency of the colours, made more intense by the “spray” technique, lends the work a chromatic and luminous vibrancy that evokes an unlimited space, a depth which frees the paper from its flat, two-dimensional limits. The notion of a spatial “infinite” was to be at the centre of a lesson given at the Bauhaus in 1932, in which Kandinsky described ratios of distance in painting and drawing his students’ attention to what he defined as the “cosmic order”. He then took as his model the open structure of a star system and, within it, pointed up the presence of “groups” of “nebular matter” which he likened to points in a coloured mass; and again, the presence of limited masses of greater sizes and of bands extending from star to star as well as “small globular masses” (W. Kandinsky, Tutti gli scritti, edited by P. Sers. Milan, Feltrinelli, 1973, p. 293). It seems that we are observing the very movement of a formal and chromatic expansion of the spaces between the splotches of blue and yellow – elements of colour perceived by Kandinsky as being perennially separating – of the background of our work, and to perceive the tensions among the linear elements that thrum their agile, flexible, sonorous, lively counterpoints.