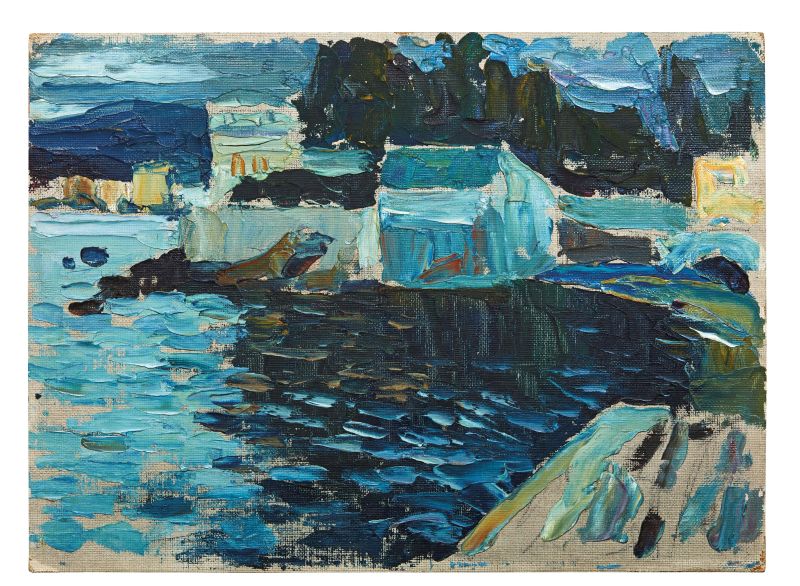

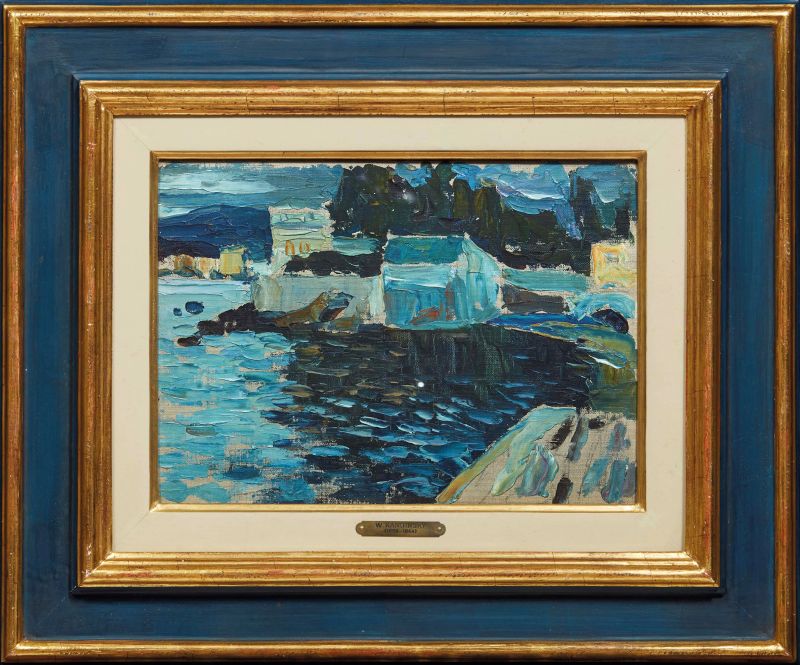

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

SESTRI-ABENDS

1905

olio su cartoncino telato

cm 23,8x32,8

sul retro: iscrizione di Gabriele Münter “Kandinsky Rapallo 1906”

SESTRI-ABENDS

1905

oil on canvas board

9 3/8 by 12 7/8 in

on the reverse: inscription by Gabriele Münter “Kandinsky Rapallo 1906”

Esposizioni

Kandinsky, Gabriele-Münter-Stiftung und Gabriele Münter, Stadtische Galerie, Munchen, 19 febbraio – 31 marzo 1957, n. 46.

Bibliografia

H.K. Roethel, J. Benjamin, Kandinsky: catalogue raisonné of the oil paintings. I. 1900-1915, London 1982, p. 154, n. 141.

Dopo un viaggio in Tunisia, Kandinsky aveva visitato diverse località italiane, soggiornando sulla costa ligure di Levante. Insieme a Gabriele, sua compagna di vita, si era trattenuto in Liguria dalla metà del mese di dicembre 1905 sino all’aprile 1906. I suoi spostamenti tra Nervi, Sestri Levante, Santa Margherita e Rapallo sono documentati da accurati disegni a matita nei taccuini di viaggio, ora a Monaco di Baviera (Stadtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus) e da intense impressioni pittoriche, spesso dipinte su piccoli supporti di cartone telato, come appunto la nostra opera. Il colore per Kandinsky, sin dalla sua prima attività, ebbe una valenza trascendente e spirituale, come energia capace di influenzare la percezione e le emozioni. Sarà l’elemento attraverso cui narrare la storia del proprio sviluppo artistico: ≪A partire dal 1900 il mio ideale era: fare un quadro estremamente drammatico, un quadro tragico. Ho dipinto una quantità di quadri di questo tipo. Fino alla Rivoluzione. In Ottobre ho veduto la Rivoluzione dalle mie finestre. Ho sentito in me una grande tranquillità d’animo. Invece del tragico, qualcosa di tranquillo e organizzato. I colori sono diventati, mi pare, molto più vivi e più dolci. Invece dei toni profondi e scuri di prima≫ (Intervista del luglio 1921, cit. in G. C. Argan, Kandinsky e la Rivoluzione, in Wassili Kandinsky. 43 opere dai Musei Sovietici, catalogo della mostra a cura di C. Terenzi, Roma, Musei Capitolini, 12 novembre 1980-4 gennaio 1981, Cinisello Balsamo, 1980, p. 14). Sestri-abends non è certo un quadro “tragico”, ma in esso vive quel desiderio, quasi quell’ansia di profondità, che Kandinsky ricercava davanti allo spettacolo della natura, tentando di strapparle il segreto della sua bellezza. La piccola veduta serale dipinta da Kandinsky colpisce per la concentrata emanazione di luce fredda della gamma prescelta, che fa della scena quasi un “notturno”, nel senso classico della intonazione vespertina dell’ora. Anche se la visione appare costruita con attenzione al dato naturale, il dipinto non è una semplice “impressione” di un luogo e di un’atmosfera. Esso manifesta l’intenzione dell’autore di esprimere attraverso mezzi pittorici un analogo della realtà, “impregnata” della propria sensibilità e della propria presenza. Dopo gli studi accademici con Franz von Stuck a Monaco di Baviera, Kandinsky guardò alla cultura impressionista e al postimpressionismo, distaccandosene. A questa data egli appare dedito a fissare l’eco intimo delle proprie percezioni nella propria visione interiore, per forma, per luce e colore ben distante dalla riproduzione ottica di un’impressione. L’artista raffina la propria sensibilità cromatica a contatto con la natura, attratto dall’esperienza spirituale che essa permette. La stessa descrizione del dato naturale non è prioritaria, come avviene per esempio nei piccoli schizzi lasciati nei taccuini di viaggio – più minuti e precisi nel disegno e nella definizione dei dettagli – rispondendo alla scopo di fissare i particolari osservati. La libera interpretazione luminosa e cromatica della scena naturale nella stesura pittorica, invece, si avvale di scelte sintetiche più risolute, sulla spinta dell’emozione per il colore. Lo scuro specchio d’acqua, il cielo venato di bagliori, la massa cupa della vegetazione del promontorio insieme agli scogli sono espressi in una chiave di rapporti affidata al solo blu di Prussia. Rileggiamo cosa scriverà Kandinsky, anni dopo, sul potere attrattivo del blu: ≪L’inclinazione del blu all’approfondimento è così grande che proprio nelle tonalità più profonde diventa più intensa e acquista un effetto interiore più caratteristico. Quanto più il blu è profondo, tanto più richiama l’uomo verso l’infinito, suscita in lui la nostalgia della purezza, e infine del sovrasensibile≫.

Following a trip to Tunisia, Wassily Kandinsky visited a number of localities in Italy and spent time on the Riviera di Levante in Liguria. With Gabriele Münter, he stayed in Liguria from mid- December 1905 until April 1906. The artist’s wanderings between Nervi, Sestri Levante, Santa Margherita and Rapallo are documented by accurate pencil drawings in his travel journals, (now in the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus of Munich) and by forceful pictorial impressions, often painted on small canvas panel supports as is our work. From the beginning of his life as an artist, colour had a transcendent, spiritual valence for Kandinsky, as energy capable of influencing perception and emotions. It was the element in which to narrate the history of his own artistic development. In 1921, he said that since 1900 his ideal had been to paint a highly dramatic picture, a “tragic” picture and that he did indeed paint a number of pictures of this type. «Until the Revolution. In October, I saw the revolution from my windows. I felt within myself great peace of soul. Instead of the tragic, something peaceful and organized. The colour in my work became brighter and more attractive, in place of the previous deep and sombre shades». (Interview given in July, 1921, cited in G. C. Argan, “Kandinsky e la Rivoluzione” in C. Terenzi, ed., Wassili Kandinsky. 43 opere dai Musei Sovietici, catalogue of the exhibition in Rome, Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori, 12 November 1980 – 4 January 1981. Cinisello Balsamo 1980, p. 14). While certainly not a “tragic” painting, Sestri-Abends harbours that desire, that quasi-anxiety to achieve the depth for which Kandinsky searched in the spectacle of nature as he tried to wrest from her the secret of her beauty. What is perhaps most striking about this small evening view painted from a vantage on the Baia del Silenzio of Sestri Levante is the concentrated emanation of cold light in a preselected range which almost makes the scene a “nocturne” in the classical sense of a section of the night office of the liturgy of the Hours. Even though the vision seems to be constructed with attention to the natural datum, the painting is not a simple “impression” of a place and an atmosphere. It manifests the author’s intention to use pictorial means to express an analogue of reality “impregnated” with his sensibility and his presence. After his academic studies with Franz von Stuck in Munich, Kandinsky looked to Impressionist and post-Impressionist culture, but stepped away from both. At that time, he seemed to be intent on securing the intimate eco of his perceptions in his inner vision, which in terms of form, light and colour was decidedly far removed from optical reproduction of an impression. The artist refined his chromatic sensibility in contact with nature; he was attracted by the spiritual experience that nature permits. Description of the natural datum was not a priority, as instead was the case in the sketches in the travel notebooks – more minute and precise in line and definition of detail – since their function was to fix observed details on paper. His freer interpretation of the light and colour of the natural scene in his painting is instead based on pondered synthetic choices carried along by his feeling for colour. The dark surface of the water, the sky veined with lightning, the murky mass of the vegetation on the promontory, even the rocks, are expressed in a relational key entrusted in its entirety to Prussian blue. Years later, a propos of the attractive power of blue, Kandinsky wrote, «The inclination of blue towards depth is so great that it becomes more intense the darker the tone, and has a more characteristic inner effect. The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural».