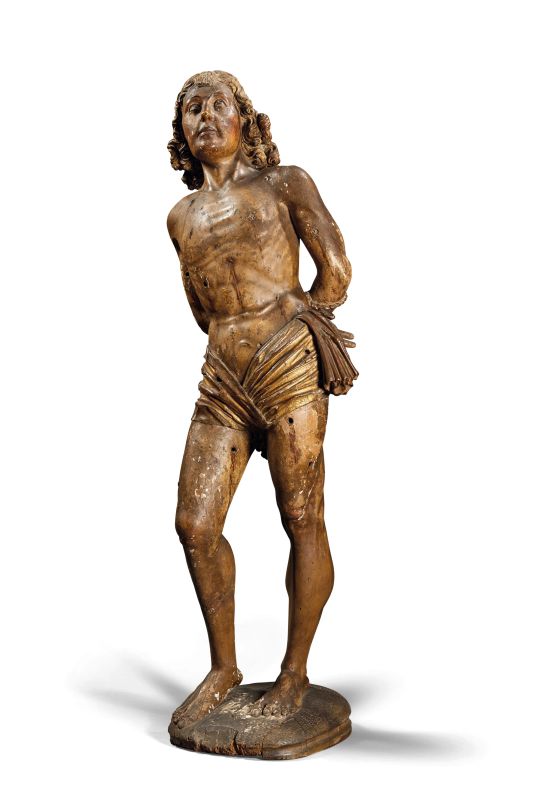

Maestro del San Sebastiano di Cascia (Master of the Saint Sebastian of Cascia)

(sculptor of German origin active in Umbria during the last quarter of the 15th century)

SAINT SEBASTIAN

polychrome wood, 148x52x40 cm

An export licence is available for this lot

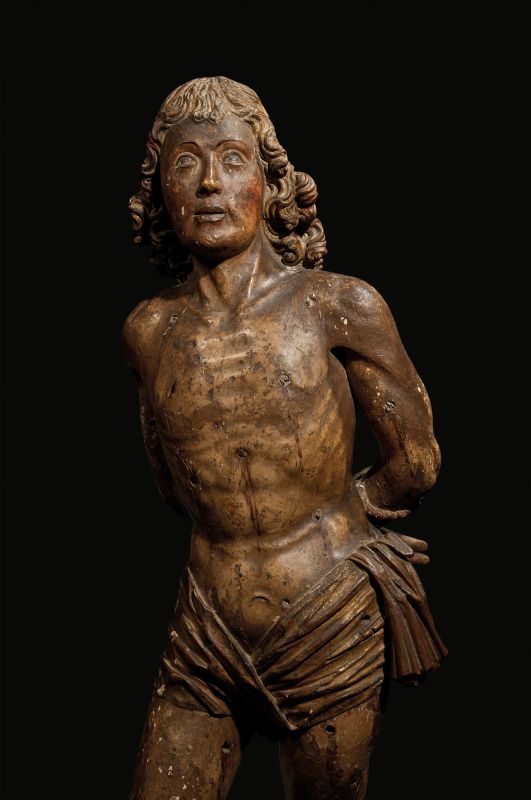

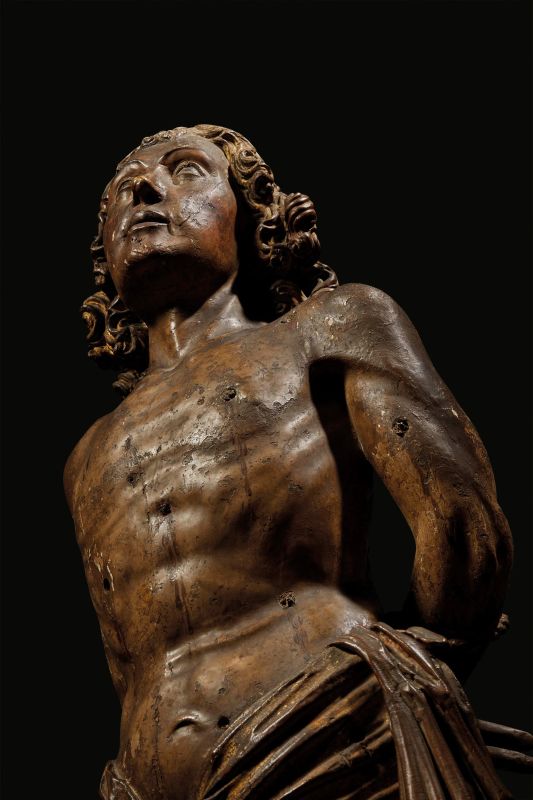

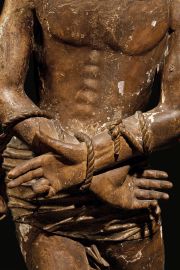

In this fascinating and unusual effigy of the popular martyr – invoked as a protector against plagues – the once athletic body of Saint Sebastian’s (Narbona 256 – Rome 304) is thinned by suffering. Sebastian was a young Roman officer whom the emperor Diocletian condemned to death for having spread the Christian faith among the troops. His body, pierced by arrows (originally set into the statue) shot by his fellow soldiers, arches back bending his torso to the right as if contracted by a sharp spasm of pain while his head is turned heavenward and his face expresses serene acceptance of his horrible torture. The marked naturalism of the harsh image, with the taut tendons and muscles, the swollen veins and the texture of the skin, is gentled by the grace of his facial features, and then is rendered more stylized and refined by the metallic carving of the thick hair with the symmetrically arranged springing spiraling curls. The workmanship on the loincloth (with its graffito gilding – that may be original like the gilding on the hair and polychrome flesh tones), developed as a sash gathered into tight, narrow folds is equally elegant and masterful. The rendering of the right hand is unusual: it is tied to the left behind his back with bent pinky and ring finger displaying the number three presumably alluding to the Trinitarian dogma which developed during Sebastian’s life and was proclaimed as doctrine by the Council of Constantinople in 381, not too long after his death.

Most of the formal peculiarities such as the arched posture, the anatomical realism, the curly hair, the fan-like shirring of the loincloth clearly make this piece comparable to another intriguing statue of Saint Sebastian in the Museo di Palazzo Santi in Cascia in Valnerina – the Nera River Valley (fig. 1) (from a confraternity of flagellants dedicated to Sebastian at the church of Sant’Agostino), which, though widely discussed in the scholarly literature, has not yet received a definitive attribution (E. Mancini, in Museo di Palazzo Santi. Chiesa di Sant’Antonio Abate, ed. by G. Gentilini and M. Matteini Chiari, Florence 2013, pp. 112-113 n. 200, with previous bibliography). One issue – the authorship of the Saint Sebastian from Cascia and other statues related to it, examined with lively curiosity in recent studies on sculpture in Umbria that will definitely find new vital lymph in the heretofore unpublished statue presented here that may be perhaps attributable to the same artist or his close circle, albeit at a later time as suggested by the bizarre expressionistic vein that dominates the Cascia figure in favor of a more moderate and classicized tone in keeping with a dating around the turn of the century.

Without delving more deeply into the issue, it is important to mention that the statue from Cascia – initially attributed to the famous Venetian sculptor, Antonio Rizzo who is documented as having fled to Ancona and the nearby Foligno in 1498 - , had already been compared by Geza De Francovich (“Un gruppo di sculture in legno umbro-marchigiane”, in Bollettino d’Arte, VIII, 1929, pp. 418-512) to other wooden statues of Saint Sebastian in the Valnerina and southern Umbria. He recognized “schemas and forms which in a certain sense are typical of late fifteenth-century Paduan-Mantegnesque naturalism but viewed and interpreted via Antonio Rizzo’s personality”, similarly to the way Paduan painting was brought into and spread through the Umbrian-Marches territories by Carlo Crivelli and Niccolò Alunno. Among these, the Saint Sebastian from the parish church of Muccia (fig. 2), along the Apennine pass that leads from Valnerina to Camerino, seems the most similar to the statue from Cascia and the one presented here because of the bent and off balance pose, while the statues from the Terni area, in the churches of San Francesco at Sangemini (now in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia), the convent of San Francesco in Stroncone, San Pietro at Collestatte (fig. 3) and Santa Maria della Misericordia in Terni (now in the Museo Diocesano) (fig. 4) – the last two added to the group by Lorenzo Principi (“Il Sant’Egidio di Orte: aperture per Saturnino Gatti scultore”, in Nuovi Studi, XVII, 2012, 18, pp. 101-128, p. 127 note 67) who also mentions another in the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Oberlin (Ohio) – are characterized by the crossed legs derived from the famous statue Pothos by Scopas. On the other hand, notwithstanding the features shared by the group from Cascia – with each other and those from the Terni group, in all these sculptures we find typological and qualitative variations that up to now have not encouraged scholars to put together homogeneous nuclei that could be attributed to one artist.

We must, however, mention that the several attribution hypothesis advanced for the Saint Sebastian from Cascia (fig. 1) include Nicola di Ulisse da Siena, a well-known painter who was very active in Valnerina during the middle of the fifteenth century and the sculptor Battista di Barnaba da Camerino, a close collaborator of Donatello documented at the court of Mantua on several occasions, in Perugia in 1454 and from there in the Marches until the 1470s (see Mancini, op. cit.). However, the recent and growing trend (C. Sapori, in Arte e territorio. Interventi di restauro. 4, ed. by A. Ciccarelli, Terni 2006, pp. 277-286 n. 30; Principi, op. cit.; G. Gentilini, “La scultura nelle raccolte museali e nel territorio di Cascia”, in Il Museo di Palazzo Santi, cit., pp. 15-24, p. 19), that recognizes a figurative tradition that can be tied to the German carvers who were active in those areas during that time in the eccentrically intense expression, in the meticulous attention to anatomical details, the elegantly stylized hair and the technical virtuosity characterizing the pieces we have mentioned. One of the most outstanding was Giovanni Teutonico (Giovanni di Enrico da Salisburgo), documented in Perugia, Terni and Norcia between 1478 and 1498 and known for having produced many crucifixes – objects favored by the Franciscans. In fact, Sara Cavatorti (Giovanni Teutonico. Scultura lignea tedesca nell’Italia del secondo Quattrocento, Perugia 2016, pp. 67-71, p. 222 n. E.II.11) has plausibly ascribed the Saint Sebastian in Terni (fig. 4) to him, finding support for the attribution in local sources.

Giancarlo Gentilini and David Lucidi