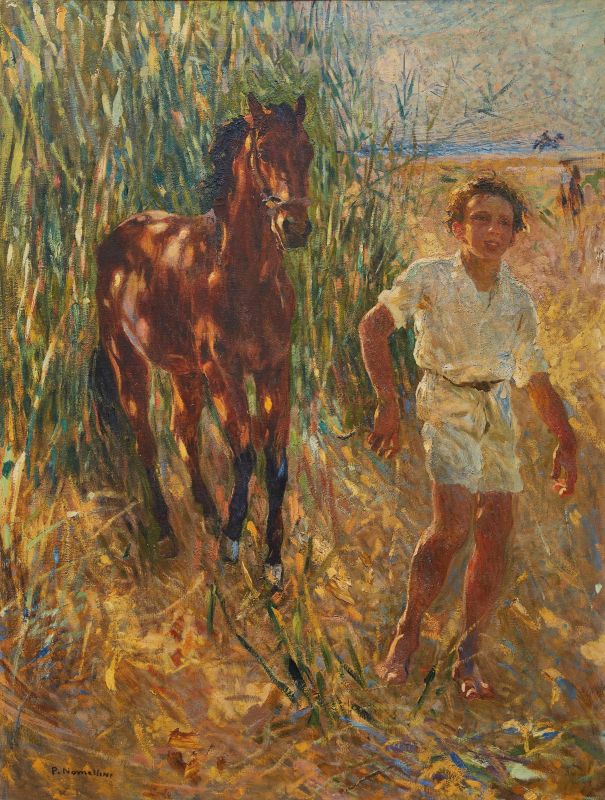

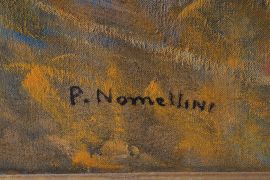

Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Firenze, 1943)

Plinio Nomellini

Plinio Nomellini

(Livorno 1866 - Firenze 1943)

THE COLT

oil on canvas, 166x129 cm

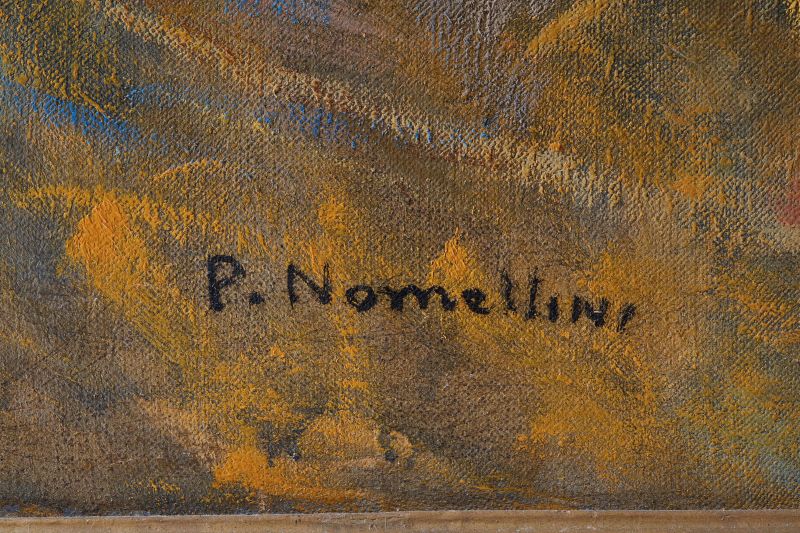

signed lower left

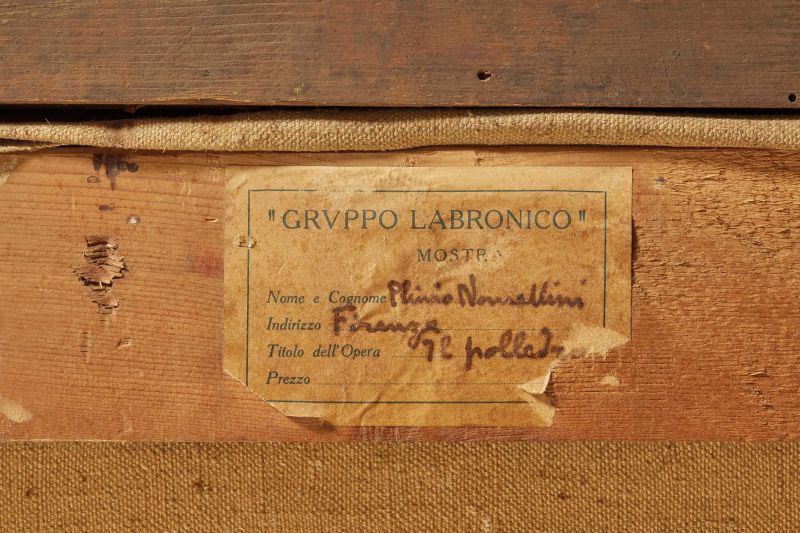

on the reverse: label of the exhibition of the Gruppo Labronico and of the exhibition I colori del sogno

Provenance

Galleria Pesaro, Milano

Private Collection

Exhibitions

XVIII Mostra del Gruppo Labronico, Milano, Galleria Pesaro 23 aprile - 4 maggio 1932

IV Mostra Sindacale Livornese, Livorno, Bottega d'Arte, ottobre - novembre 1932

Mostra personale, Genova, Galleria d'Arte, gennaio 1934

V Esposizione d'Arte, 88a Mostra Sociale Società delle Belle Arti, Montecatini Terme, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, giugno - ottobre 1934

Mostra di artisti toscani, Cesena, Biblioteca Malatestiana, 3 - 24 settembre 1939

Plinio Nomellini. I colori del sogno, Livorno, Museo Civico G. Fattori - Firenze, Galleria d'Arte Moderna, luglio - ottobre

1998

Bibliography

XVIII Mostra del Gruppo Labronico, catalogo della mostra (Milano, Galleria Pesaro 23 aprile - 4 maggio 1932), Livorno 1932, n. 89

IV Mostra Sindacale Livornese, catalogo della mostra (Livorno, Bottega d'Arte, ottobre - novembre 1932), in "Bollettino di Bottega d'Arte", XI, 10, n. 12

Mostra personale, catalogo della mostra (Genova, Galleria d'Arte, gennaio 1934), Genova 1934, n. 4

V Esposizione d'Arte, 88a Mostra Sociale Società delle Belle Arti, catalogo della mostra (Montecatini Terme, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, giugno - ottobre 1934), Firenze 1934, n. 115

Mostra di artisti toscani, catalogo della mostra, (Cesena, Biblioteca Malatestiana, 3 - 24 settembre 1939), Cesena 1939, n. 7

Plinio Nomellini. I colori del sogno, catalogo della mostra (Livorno, Museo Civico G. Fattori - Firenze, Galleria d'Arte Moderna, luglio - ottobre 1998) a cura di E.B. Nomellini, Torino 1998, n. 66

The painting Il polledro we present in this sale was exhibited for the first time at the Labronico Group exhibition in Milan in 1932 at the Pesaro Gallery. Nomellini wrote the preface to the catalog which we report here:

In our day, developments in art are happening so quickly, one after the other, so that comparing them with those that occurred prior to our era they seem enormously delayed. Certainly, much of what we celebrate today will soon become short-lived; since there is no use in belonging to a movement to move art ahead if the values and intentions are not sufficient for bringing new expressivity of language suited to reflecting images unusual for the customs that we develop ourselves and, the heights to which we aspired.

On the other hand, it is wrong to relegate concepts that are no longer suited to our ways of feeling to the past. If anything, it will be an impetus to see how, in the past art moved ahead when it turned to new frontiers. Remaining motionless in the memory of past glories means withering and decay.

This applies to the fact that the Livornese artists gathered here in the Galleria Pesaro, prove with their works that they are not inclined to listen to distant echoes. Livorno, in fact, is not a city with a great and old artistic tradition. The memory of remains of the Etruscan tradition that emerged from the land where Livorno was established in 600 [seventeenth century] soon disappeared; and from the rebirth the Medici did not draw anything if not eloquent imitators , not initiators: Vasari, Buontalenti, Tacca, Bandinelli, Cantagallina. Except for [Giuseppe Maria] Terreni, successful fresco artist, between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Livorno, from the Romantics [Giuseppe] Baldini to [Enrico] Pollastrini, did not make any strong statement in art if not for Giovanni Fattori’s valid stimulus.

However, it is right that the warning be addressed to those who are making their names, because in order for art to be ennobled they must faithful to the teachings of the great Master and that poor habit not be perpetuated especially on the part of those who had not known the man and incorrectly interpret his art, saying that they are the pupils and standard bearers of his glory. The first to disapprove would be Fattori himself, the man who incited to go beyond, saying that we must create new words to expound sensations not yet experienced.

To be truthful, in this exhibition it is obvious that we Livornese work without permitting any dogmatic dictates to dull and weaken [our] inspiration and effort. If we remove the loving influence of Fattori and the Macchiaioli, no foreign lymph mixes with and clouds the pure water springing from a fresh vein. Not even Modigliani, with tormented thoughts directed toward visions in which madness, vice, and pain transfigured the soul, was touch by the mad desire of not appearing himself when, especially in moments of tranquility he conceived images of purity.

Therefore, simple and delayed art? No. Pure and serene, appropriate for telling of the charm of the district that surrounds our beloved city: the maquis, the hills, the vast expanses of wheat; the olive groves made green by the salty wind; the bustling port, the rocks perfumed by the algae.

But sooner or later, these restful musings will give rise to one who sings of the feats of this bold seafaring people whose blood exuberantly mixed with different races which, from the entire Mediterranean brought the gifts of the Eastern civilizations to Livorno.

If this were not to happen, we will sadly have to think of what the coming generations could say of the paintings – and rightly so – that in these years, our country imported huge amounts of bananas and coconuts.

Plinio Nomellini

The colors of dreams

Plinio Nomellini often painted outdoors in his pine grove with strutting peacocks, and graced by the exotic plants he received from his anarchist friend, the agricultural expert Giovanni Rossi, and enlivened by his wife Griselda, and children Vittorio, Aurora and Laura, who are featured in many delightful paintings set in Torre del Lago, or in Versilia “Prime letture”, 1906; “Baci di sole”, 1908; “Mezzogiorno”, 1912; “Bambine al mare”, 1912/1913. The canvas could be on an easel or nailed to two posts driven into the ground, in the shade of the pines, or with supports lapped by the sea. The tree trunks glistened with touches of yellow, of crimson, of cobalt [blue], Nomellini said, “I make them sing”. Many friends paid him visits Eleonora Duse, Gabriele d’Annunzio, Giosuè Borsi, Giacomo Puccini, Grazia Deledda, Isadora Duncan, Moses Levy. For a “first time” visitor, for journalists, for critics, leaving his studio filled with works from the present and the past, Jean Genet’s words when he left Alberto Giacometti’s atelier in Paris, “Outside nothing seems real” could have been equally true.

Many of the paintings from his years in Versilia were shown at the Secessione in Rome, born to contrast the early exhibitions of the Amatori e Cultori, that were not very innovative in reality, but put the Italian artist close to Matisse, Cézanne, Klimt, Rodin, Schiele, Munch, Signac, Vuillard, and Zuloaga.

The interventionist episode of D’Annunzio’s speech at the unveiling of the monument by Eugenio Baroni at Quarto dei Mille (Genoa), for which Nomellini had designed the poster, the war, the patriotic paintings, “Alle porte d’Italia”, “Vittorio Veneto” from 1918, were followed by public works related to Italy’s new political tide. But in these paintings Nomellini did not reach the tension of “Orda” or “Migrazione d’uomini”, executed in the early years of the century. The advancing crowd is practically one, almost faceless, a single spirit reaching out to create a new, ideal world. The crowds in the paintings that glorify fascism such as “Ignoto militi” (1922). “Incipit nova aetas” (1924) are group of figures in the foreground with well-defined faces as if giving them identities could provide powerful motivation.

However, the public paintings are just one aspect of Nomellini’s life and oeuvre. His work from the 1920s on was neglected by the critics who, being more and more interested in studying painting movements did not see him as participating in the twentieth century movements. But looking at paintings such as “I corsari” (1924), the landscapes of Capri, Quercianella, Ischia, Elba, the island where the artist decided to build a house in the then deserted gulf of Marina di Campo, with fresh eyes we can see the vitality and creative power he always maintained. The small landscape impressions are closest to our hearts, but perhaps the paintings in which Nomellini captured fantasies that always guided him are the ones that acquired greater importance. This exhibition concludes with two paintings chosen because they are emblematic of this: “Scena piratesca” and “Corsaresca” from 1940. They are parallel in theme and manner of interpretation. It is surprising that up to the end the artist never abandoned his desire to transform reality. The pirates who seem to become one with the rock like a Daphne being transformed into a laurel tree, or the waves that become horses as painted by Walter Crane show us a Nomellini who had the good fortune of never losing the desire to transform images of the world into images dreamt.

Nomellini became a very famous artist. He had a solo show of forty-three paintings at the 1920 Venice Biennale and he showed at all of the most important exhibitions in Italy and abroad. He was very close to the painters from Livorno and in 1928 became president of the Gruppo Labronico and with his influence furthered the success of their exhibitions. He enjoyed writing the introductions for the group’s exhibitions and reminiscences of his and his friends’ lives in the press. In 1934 he traveled to Tripolitania. They were neither the times nor the places of Matisse’s early twentieth-century journeys to Morocco, but his spirit, always ready to descend into the realm of the fantastic, was touched by the vibrant traces of ancient ruins and by the swarming Arab markets. Nomellini, who was so opposed to fossilization in the academies also taught. The time had come for him to be a teacher, not to try new things but to think of what his life had been and to delve ever deeper into the study of the inner world he had tried to imprison and at the same time reveal in his paintings.

In 1934, preparing for his solo show in Livorno, he wrote some notes about himself for Riccardo Marchi who was to write the presentation. They can be considered the farewell of a man who was trying to understand himself and look at his work and life with humility.

Out of principle, my faculties were always driven so that the expression of my art be considered – in the past, present and in the future - as springing from my character which by nature and instinct is tumultuous. That is why I yielded to others’ ideologies, especially when they reflected fleeting transitions from one mode and to another; which for those who look into the essence of things, have nothing to do with art that evolves, in the periods in which the sense of hope, the predictions of the race proceed with just one reason: to bring humanity the joyful comfort of beauty. Beauty which can, according to the times and customs, change its face, on which all cast their eyes to lighten the spirit. Therefore, in my case, it is not the case of aesthetic updating and embellishments unsuited to my way of being. Destiny forced me to lend my voice. This voice has to have the sound that echoes in my heart, because otherwise it would be a voice that does not match the workings of my spirit. As time passes, my painting will seem distinct from what was usually done by others during the period that I executed many works which, upon now looking back, surprise me by their numbers. And yet, it seems that I have not yet composed that song of color that I long for and dream. And it will never come to pass that I be satisfied with the fact that, perhaps beyond, in a new life, far from the wretched circumstance of having to live in the human community, in the deep abysses where the phosphorescence and glimmering of the stars compose music in the endless silence, I find the calm to create in unison with the slow growth of the stars and of new lives, the way and feeling to express the beautiful poem and ringing song with solemn words.

Eleonora Barbara Nomellini (a cura di), Plinio Nomellini. I colori del sogno, Livorno 1988, pp. 18-19