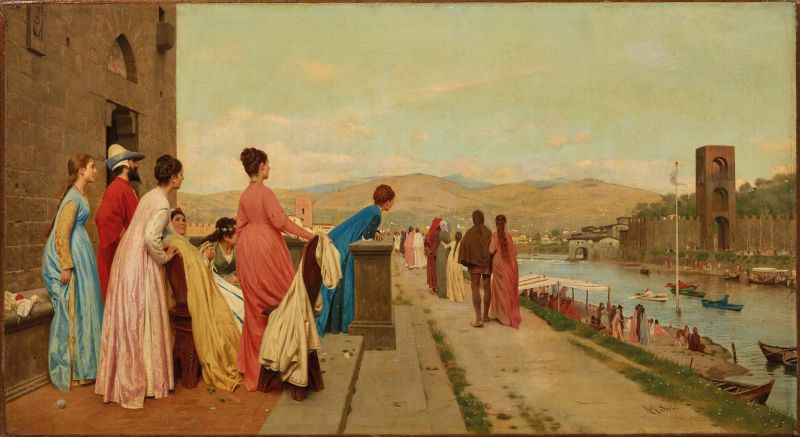

Raffaello Sorbi

(Firenze 1844 - 1931)

THE REGATTA ON THE ARNO

oil on canvas, 40.5x73.5 cm

An export licence is available for this lot

Bibliography

A. Parronchi, Raffaello Sorbi, Firenze 1988, n. 112

Raffaello Sorbi’s Regata in Arno (The Regatta on the Arno) is an excellent example of that production of costumed genre scenes to which the artist turned in the 1860s and 1870s. The painting shows us a broad panorama of the area to the south of Florence, surrounded by hills, as Sorbi imagined it to have looked in the Middle Ages.

From the terrace of a medieval building, a cheerful gathering of smiling, elegantly-coiffed young women in brightly-coloured dress watches the regatta disputed by the traditional navicelli on the Arno River. The event attracts ladies and knights, who flock to the riverbanks in search of the best observation post for viewing the competition. Upstream, on the right bank of the Arno, we note the Torre di San Niccolò, the oldest of the city gates, which takes its name from the neighbourhood in the Oltrarno area. Built in 1324, probably to plans by Orcagna, it is the only one of Florence’s gates to have retained its original height. At the sides of the tower, we note the city walls and the pescaia, the weir which denied access to the river by enemy vessels coming from the east (to the west, the same functions were performed by the Santa Rosa weir), an ideal continuation of the city walls to the Zecchia Vecchia tower and the crenulated walls on the left, behind the young women. Another function of the pescaia was to channel and regulate the level of the waters to guarantee sufficient and constant flow to the fulling mills, the tenters’ establishments, other manufactories and the tanners and dyers who operated in the area.

The perspective in the painting is rigorous; the graphic layout and the alternating planes respond to what would seem to be the artist’s need to construct a sharply-defined scene while delicate layers of colour soften the sign. The lesson taught by the Macchiaioli painters is apparent in the hill country composing the background but stands in contrast to the clear brightness of the foreground light and colours.

The work can be dated to 1874-1876, years in which Sorbi painted analogous subjects and similar compositions. Here, we note the same figures of young people gathered in merry, carefree groupings as in Una terrazza sull’Arno (A Terrace on the Arno) oil on canvas, 51 x 66 cm, signed and dated 1874, Concertino all’aperto (Florentine Concert) oil on canvas, 50 x 63 cm, 1875 and Il Decamerone (The Decameron) oil on canvas, cm 45.5 x 88.7 cm, 1876.

THE PALIO DE' NAVICELLI

The Arno River has always played a central role in the life of the city of Florence, as the innumerable views of Florence by artists who have worked in Tuscany since the Middle Ages clearly attest. It is thanks in part to this legacy of art that we are able to reconstruct the history of the relationship between the city and its watercourse. The Arno was perfectly integrated into city life, as the fulcrum of Florentine economic activity and as an identifying element, a mirror reflecting the image of the city. Beginning in 1250, the Palio de’ Navicelli (or ‘delle Barchette’) boat race was held every year on 25 July in honour of ‘San Jacopo’ (as the Florentines called the apostle Saint James the Greater). The starting line for this city regatta was the bank over which the apse of the church of San Jacopo Soprarno still juts on its supports – and in fact, the burden of paying the expenses of the Palio fell to the prior of the Cappellanìa (chapel) attached to the church. For centuries, it was an important event in Florence, hotly contested by the crews of small wooden boats of the type used by the renaioli, the ‘sand diggers’ who provided the sand used by the city’s construction workers. Each of the four city districts – Santo Spirito, Santa Maria Novella, Santa Croce and San Giovanni – competed with a boat of this type, which remained unchanged for centuries. In the painting, in fact, we note four boats, in four colours, one for each of the four neighbourhoods: white, red, blue and green. In the late 1700s, even the regatta fell prey to the reforms instituted by Grand Duke Peter Leopold I of Lorraine, and the ancient regatta was abandoned. The tradition has, however, recently been revived by the City of Florence in other guises.

It would seem that the idea of celebrating the Apostle’s feast day with a regatta derives from a legend having to do with the relics of the decapitated saint: as the story goes, following his martyrdom, James’ disciples placed his remains in a sail-less, rudderless vessel (like those used in the Palio), which nevertheless miraculously made its way to the coast of Galicia, in Spain, where they were interred at the locality which later became Santiago de Compostela. Another version recounts that the race on the river was instituted to imitate the naumachie of ancient Rome, just as the Palio or Corsa dei Cocchi race, which was run in Piazza Santa Maria Novella, was in truth nothing more than a version of the chariot races held in the Circus Maximus in ancient Rome.

The slow and stately progress of the boats toward the finish line left ample time for the spectators to place bets while urging on their favourites with deafening cries. The quanters, in turn, worked furiously to cross the finish line in first place and thus win the ‘palio’, the painted banner awarded to the winner.