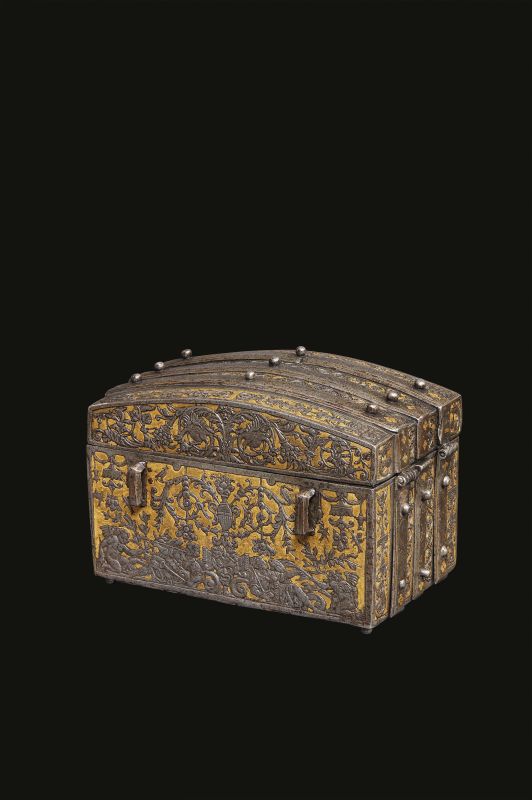

FORZIERINO, BOTTEGA MILANESE, SECONDA METÀ SECOLO XVI

CASKET, MILANESE WORKSHOP, SECOND HALF OF THE 16TH CENTURY

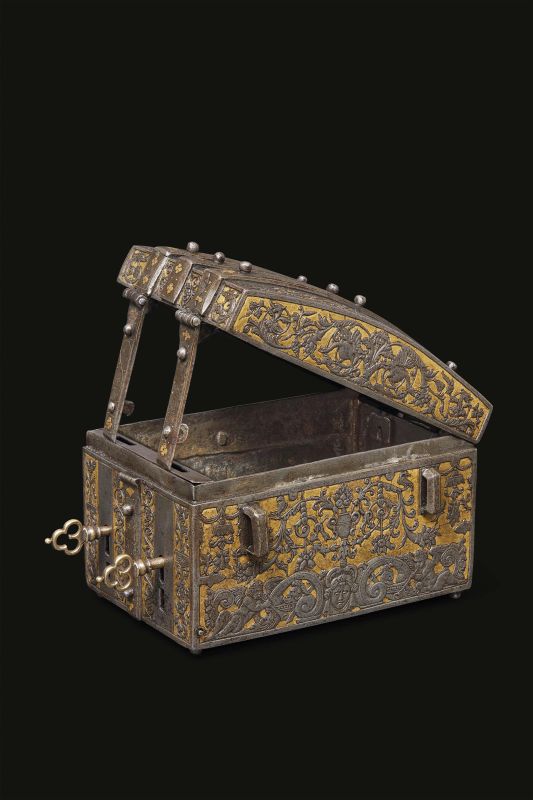

iron, etched decorations on gold ground depicting grotesques with masks, figures, animals, plant garlands; double lock on the front concealed by plates that open with a snap mechanism; pair of loops on both long sides; 10.2 x 16 x 11.4 cm

Comparative literature

P. Lorenzelli, A. Veca (ed. by), TRA/E. Teche, pissidi, cofani e forzieri dall’Alto Medioevo al Barocco, Bergamo 1984, pp. 254-258;

B. Chiesi, I. Ciseri, B. Paolozzi Strozzi (ed. by), Il Medioevo in viaggio, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 20 March - 21 June 2015), Florence 2015, pp. 198-199;

S. Leydi, “Mobili milanesi in acciaio e metalli preziosi nell’età del Manierismo”, in Fatto in Italia, dal Medioevo al Made in Italy, exhibition catalogue (Turin, Venaria Reale, 19 March – 10 July 2016), Milan 2016, pp. 121-137

Caskets of this type were used to hold coins, jewels or often documents or valuable books of hours, providing protection not only against prying eyes, but mainly risks incurred during travel. The contents were protected by the sturdiness of the material and by particularly complicated locks.

A rope or leather belt was threaded through the loops on the long sides to fasten the casket to a saddle or inside a bigger trunk, or let it be worn cross-body or attached to a belt on long journeys.

This type of casket is often called a “messenger box”. Given the manageable size and the large number of items that have survived, they may have been used by a wide range of people, from clergymen to students, from messengers to merchants without ruling out household use. The reference to church use is supported by the rings on the long sides that were practically made to the specifications set out in Exodus (25:25-28) for the Ark of the Covenant: “And you shall make for it four rings of gold and put the rings on the four corners”. The poles to carry the Ark were passed through the rings.

The style and type of workmanship are exactly what we see on the most beautiful suits of sixteenth-century armour made by famous Milanese armourers such as the Negrolis, Pompeo della Cesa, and Piccinino who worked for the most important families in Italy and Europe. In addition to the weapons and armour that made them famous, their workshops also produced steel or iron “luxury” goods such as chests and coin cases, mirrors, candlesticks, reliquaries, coffers, belt fittings, sword hilts, bits, stirrups, saddles and powder flasks. There is no proof that the legendary damascener Martino Ghinelli ever lived, but the existence of two important specialized workshops is documented. One was owned by Giovan Battista Panzeri, called Sarabaglia (Milan, c. 1517-1587); he was Filippo Negroli’s brilliant pupil and made items in gilded iron for Ferdinando Duca d’Alba, Philip II of Spain, and the dukes of Mantua. The other belonged to Giovanni Antonio Polacini called Romerio or Romé (c. 1527- died between 1595 and 1602).

In the middle of the sixteenth century the armourers’ workshops developed extraordinary, intense and splendid creative skills that made their wares highly sought-after throughout the world. Surfaces were entirely decorated, the areas that had previously been left “blank” became filled with damascened or painted floral and legendary motifs in a sort of spasmodic return of the horror vacui that had enchanted artists of the early Middle Ages. This trend was followed by the glorious “all’antica” armour so coveted by princes, kings and emperors for decades which gave way to the style known as heroic. Armourers no longer worked on developing new shapes, rather they used simple ones and covered them with gold. By that time the armourer was no longer a mere craftsman following rather than creating fashions: he was a true artist, on a par with the period’s great painters and sculptors because, by creating excellence, he could impose his ideas. These artists worked closely with the armourers as was the case of Leone Leoni, sculptor to the court of Charles V whose work is clearly evident on some armour commissioned by the emperor; the same can be said for his son, Pompeo, protégé of Philip II, and of Benvenuto Cellini who, working with the Negrolis, designed suits of armour for Cosimo I Grand Duke of Tuscany.

It was not only outstanding works of architecture, sculpture, and painting that made Milan the “luxury capital” of the sixteenth century. There were the extraordinary objets d’art created in the workshops of Milanese craftsmen for an elite international clientele of sovereigns, princes and nobles, courtiers, and other rich and ambitious art enthusiasts. Milanese workmanship was a guarantee for weapons and armour as well as many other applied arts including the manufacture of fine silk damask and lampas fabrics, jewellery, and enamel wares. The art of metalworking was already flourishing in the fifteenth century under the Viscontis: goldsmiths and armourers were turning out the highest quality goods. In particular, Milan was known for magnificent suits of armour that were considered the finest items in men’s fashions. The magnificent wares of famous armourers were desired by all the sovereigns, and all the princely and ducal houses. The items made in Milan during the sixteenth century are characterized by a unique blend of creative power, fine materials and extraordinary workmanship. Indeed they became hallmarks of the elites, and badges of status.

Our casket, in terms of style and form is truly a child of the artistic ferment of mid-sixteenth-century Milan. It is evidence of the Milanese armourers’ technical mastery applied to a “civilian” object that was surely made for a noble client. The lavish decorations, typical of the late Mannerist period make it possible to date this object around the second or third quarter of the century. The variety of the grotesques that differ on each side speak to the artisan’s consummate skill as he was able to combine raised masks, putti, trumpeting angels, dragons, and vases with flowers amidst plant raceme and overflowing cornucopias, garlands and birds against the gilded background through mastery of the etching technique that had already been used to decorate arms and armour in the Middle Ages.